Aga Khan museum mosque, Toronto

History

The

Aga Khan Museum, the first museum in North America devoted to Islamic art and

culture is an initiative of His Highness the Aga Khan, the 49th hereditary Imam

of the Ismaili Muslims. The project seeks to foster knowledge and understanding

both within Muslim societies and between these societies and other cultures

around the world. Dedicated to presenting an overview of the artistic,

intellectual and scientific contributions that Islamic civilizations have made

to world heritage, the Museum is home to galleries, exhibition spaces,

classrooms, a reference library, auditorium and restaurant. It houses a

permanent collection of over 1,000 objects including rare masterpieces of broad

range of artistic styles and materials representing more than ten centuries of

human history and geographic area.

Urban and Architectural

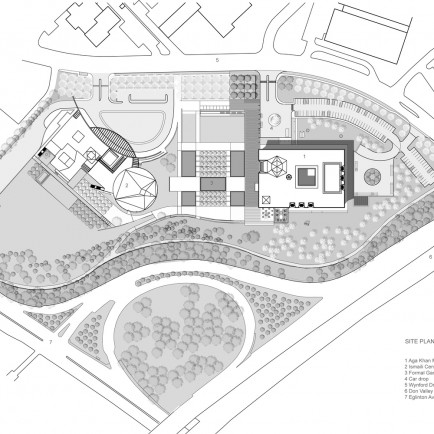

The Aga Khan Museum is one of two

buildings developed in a 6.8 hectare (16.8 acre) site together with the Ismaili

Centre designed by Charles Correa and Formal Gardens by Vladimir Djurovic. The

buildings are perched upon a small hillock that is visually prominent at the

intersection of the Don Valley Parkway and Eglinton Avenue, two significant

heavily travelled arteries north of downtown Toronto.

From the site itself, panoramic distant

views of the Toronto skyline unfold Maki and Associates carried out the Master

Plan for the entire site organizing two buildings around a Formal Garden, 100

meter wide, inspired by a contemporary interpretation of the Islamic courtyard

– the Charbaag. The Garden, an urban oasis, is positioned at the center of an

irregular undulating site while creating an informal landscaped park around the

periphery.

The Ismaili Centre, a religious, social and spiritual building for the Ismaili Community is oriented toward Mecca. The Museum, a cultural civic facility open to the general public establishes a strong dialogue with the Ismaili Centre on a central axis across the Formal Gardens. The two buildings, sacred and secular, are unified through the gardens and landscape aimed at achieving a sense of harmony in a park setting throughout the entire site

Description

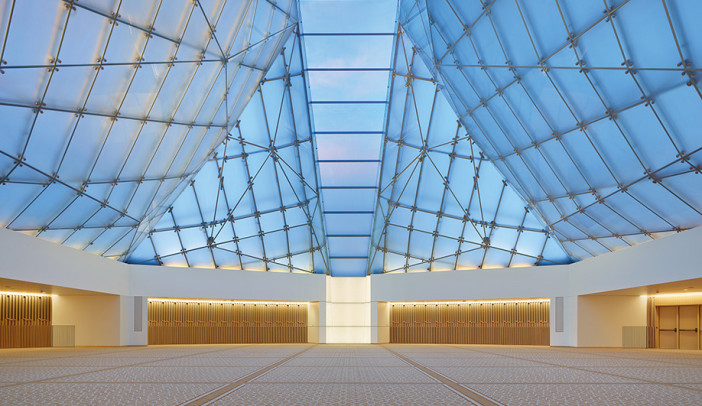

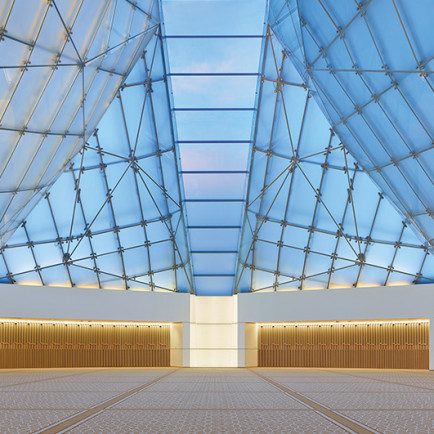

While the is less accessible to the public than the museum (during prayer times, the hall is reserved for followers of the faith), it was still designed with light and openness at its core. The front doors are set within a sweeping limestone wall, and the plan of the prayer hall is a circle.

For Correa, both are architectural metaphors of welcoming, all-embracing arms. Arriz Hassam, of Toronto’s Arriz+Co, and British firm Gotham Notting Hill collaborated on the interior finishes, which also express a sense of openness. The main lobby, meeting hall and offices are separated by transparent walls etched with a motif of Hassam’s own design, based on a fractal pattern inspired by the geometries of Correa’s prayer hall dome. The pattern is repeated on the stone floors, carpeting and screens; the composition of stars and circles alludes to both celestial divinity and earthly inclusivity.

The Ismaili Centre, Toronto, was designed to respond to the traditions of Islamic architecture in a contemporary way using modern materials. A distinguishing feature of the building is the multi-faceted glass roof of the prayer hall (Jamatkhana), that can accommodate 1,500 people, which recalls the corbelling in many of the traditional domes in the Muslim world. The glass dome, which represented a difficult technical challenge, rises to a height of 65 feet above the roof and is made of two layers of high-performance glass and fritted to deflect the heat of the sun.

A clear sliver of glass facing east toward Mecca runs down the translucent roof. The orientation of the building is determined by its urban context, which provided a grid with which to work. Set against the grid is the circular prayer hall. The prayer hall is spanned by a double layer of glass sitting on elegant structural steel trusses of various depths and dimensions. The glass rises in the shape of a cone and is pieced together to form a fractal skin. The Ismaili Centre also includes spaces for institutional, social, educational and cultural activities.

Details

Location

North York, ON M3C 1K1, Canada

Worshippers

1500

Owners

Imara (Wynford Drive) Limited

Year of Build

2014

Drawings

Map

History

The

Aga Khan Museum, the first museum in North America devoted to Islamic art and

culture is an initiative of His Highness the Aga Khan, the 49th hereditary Imam

of the Ismaili Muslims. The project seeks to foster knowledge and understanding

both within Muslim societies and between these societies and other cultures

around the world. Dedicated to presenting an overview of the artistic,

intellectual and scientific contributions that Islamic civilizations have made

to world heritage, the Museum is home to galleries, exhibition spaces,

classrooms, a reference library, auditorium and restaurant. It houses a

permanent collection of over 1,000 objects including rare masterpieces of broad

range of artistic styles and materials representing more than ten centuries of

human history and geographic area.

Urban and Architectural

The Aga Khan Museum is one of two

buildings developed in a 6.8 hectare (16.8 acre) site together with the Ismaili

Centre designed by Charles Correa and Formal Gardens by Vladimir Djurovic. The

buildings are perched upon a small hillock that is visually prominent at the

intersection of the Don Valley Parkway and Eglinton Avenue, two significant

heavily travelled arteries north of downtown Toronto.

From the site itself, panoramic distant

views of the Toronto skyline unfold Maki and Associates carried out the Master

Plan for the entire site organizing two buildings around a Formal Garden, 100

meter wide, inspired by a contemporary interpretation of the Islamic courtyard

– the Charbaag. The Garden, an urban oasis, is positioned at the center of an

irregular undulating site while creating an informal landscaped park around the

periphery.

The Ismaili Centre, a religious, social and spiritual building for the Ismaili Community is oriented toward Mecca. The Museum, a cultural civic facility open to the general public establishes a strong dialogue with the Ismaili Centre on a central axis across the Formal Gardens. The two buildings, sacred and secular, are unified through the gardens and landscape aimed at achieving a sense of harmony in a park setting throughout the entire site

Description

While the is less accessible to the public than the museum (during prayer times, the hall is reserved for followers of the faith), it was still designed with light and openness at its core. The front doors are set within a sweeping limestone wall, and the plan of the prayer hall is a circle.

For Correa, both are architectural metaphors of welcoming, all-embracing arms. Arriz Hassam, of Toronto’s Arriz+Co, and British firm Gotham Notting Hill collaborated on the interior finishes, which also express a sense of openness. The main lobby, meeting hall and offices are separated by transparent walls etched with a motif of Hassam’s own design, based on a fractal pattern inspired by the geometries of Correa’s prayer hall dome. The pattern is repeated on the stone floors, carpeting and screens; the composition of stars and circles alludes to both celestial divinity and earthly inclusivity.

The Ismaili Centre, Toronto, was designed to respond to the traditions of Islamic architecture in a contemporary way using modern materials. A distinguishing feature of the building is the multi-faceted glass roof of the prayer hall (Jamatkhana), that can accommodate 1,500 people, which recalls the corbelling in many of the traditional domes in the Muslim world. The glass dome, which represented a difficult technical challenge, rises to a height of 65 feet above the roof and is made of two layers of high-performance glass and fritted to deflect the heat of the sun.

A clear sliver of glass facing east toward Mecca runs down the translucent roof. The orientation of the building is determined by its urban context, which provided a grid with which to work. Set against the grid is the circular prayer hall. The prayer hall is spanned by a double layer of glass sitting on elegant structural steel trusses of various depths and dimensions. The glass rises in the shape of a cone and is pieced together to form a fractal skin. The Ismaili Centre also includes spaces for institutional, social, educational and cultural activities.