Abdul Rahman Saddiq (Jumeirah’s Spine Mosque)

History

Located next to the tunnel for the guargantuan Atlantis hotel, the Spine Mosque on Palm Jumeirah is the polar opposite of Dubai’s famous leisure resort. Rather than mimicking Atlantis’ overwhelming exuberance, Jordan based firm “Yaghmour Architects” has designed a building that exudes simplicity, elegance and calm. Indeed, the clean-lined cubist form represents the first contemporary mosque in the UAE, a far cry from the traditionalist designs of Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi and Jumeirah Mosque in Dubai. Standing outside the entrance, Raed Yaghmour, managing director, explains how the project came about. “We were asked by Nakheel to develop an iconic mosque on Palm Jumeirah. It was the first mosque built by Nakheel. It’s a different concept for mosques as it is modern.

Urban and Architectural

Description

We thought outside of the box.” Raed adds that the benefactor was Dawalet Siddik, who honoured her father Abdulrahman. “The official name is Abdulrahman Siddik Mosque, although we sometimes refer to it as the Spine Mosque. Nakheel shared the burden with the benefactor by providing the land and half the cost of the mosque. The total budget was AED22m, excluding the land cost, and it took around two years to construct.” Farouk Yaghmour, principal in charge, who personally oversaw the design development of the building, remarks: “Nakheel called us and said there was a limited competition to design the Spine Mosque, but we didn’t know much. We have previous mosque experience in Jordan, but mosques are not necessarily our speciality. In the beginning we started with traditional designs.

With this project we tried to AED22M TOTAL budget of the SPINE MOSQUE do a different approach and transform the typology.” He continues: “The Spine Mosque was one of the first chances to go for a different approach. We wanted to use bold, contemporary materials and we were very careful in our selection of materials and how they were put together. The rough wall contrasts with the glass.” The Spine Mosque was won after Yaghmour worked with Nakheel in 2008 on an unrealized mosque in Port Rashid. “Our first mosque design for Nakheel went to the extreme of contemporary,” adds Farouk. “We designed different alternatives with a very pure glass skin.

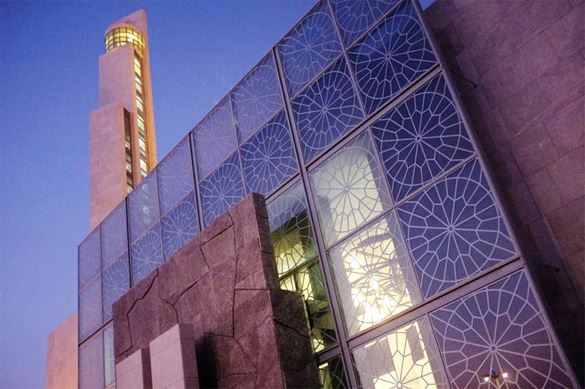

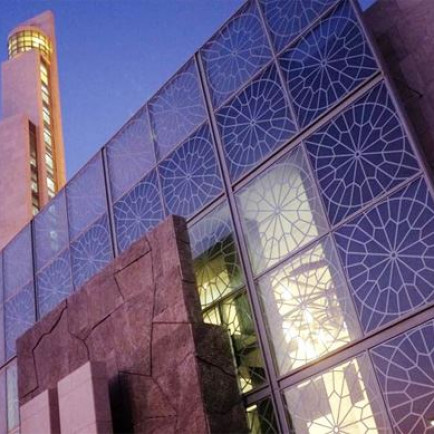

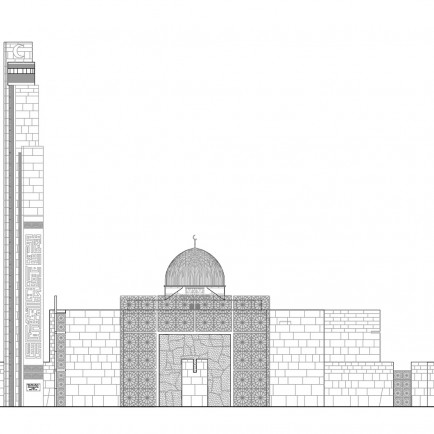

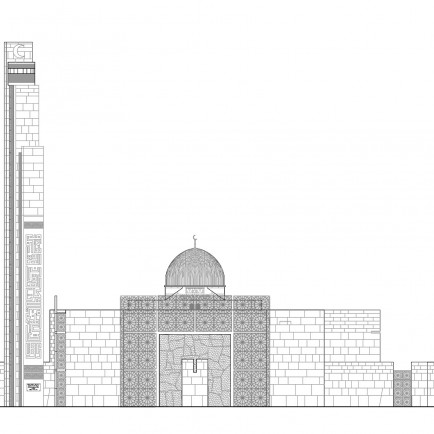

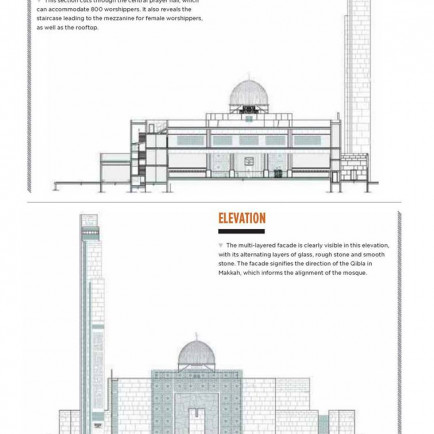

Symbolically we included the dome and the minaret in the Spine Mosque. There was no dome in the Port Rashid Mosque.” Externally, the dominant features of the Spine Mosque are the two traditional elements - the dome and a 49m-high minaret. Yet what makes the mosque really stand out is the treatment of the facade that faces the Qibla in Makkah; with its layers of rough stone and patterned glass, it appears that the building’s skin has been sliced. Raed comments: “The glass has a double skin all the way to the ground with an insert of aluminum sheet.

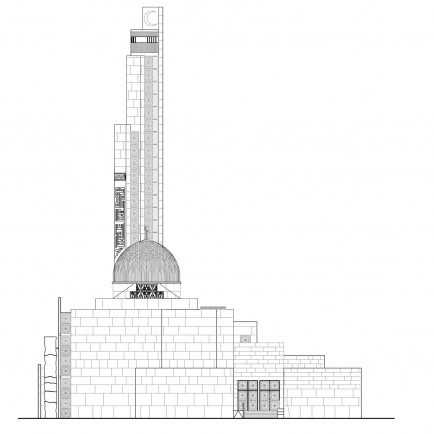

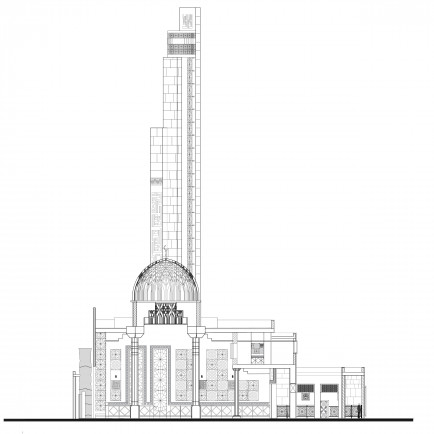

Glass panels measure 2.5m by 2.5m and each unit contains four panels, so a unit measures 5m by 5m. A layer of stone emphasizes the area for the Imam - the person that leads worship in the mosque. “We wanted it to be as natural as possible so every pieced was sized. We had a hard time putting it together as it was like a jigsaw puzzle. There is a concrete structure behind and then it was glued on top.” As well as containing a rough wall, the majority of the building is clad in a smooth beige stone. Raed reveals that the rough and smooth portions are the same Omani marble. The smooth portion is also comprised of different sized blocks and this irregularity lends a handmade quality rather than a harsh uniform aesthetic. At 49m high, the minaret soars over the surrounding area. Raed remarks that the placement of the minaret was moved following a reduction in the plot size.

“With the minaret we did not have much land to work with. The plot was reduced so we had to place the minaret in a different position. The crescent on the minaret lights up at night to signify the evening call to prayer. It can be seen from a long distance.” He adds that the initial plan included an elevator to access a viewing gallery at the top of the minaret. “The viewing gallery would have been a good thing for people to come and see.

It would have meant that the building would be used not just for prayer. Now the minaret is just a monument connecting the mosque,” he remarks. Farouk adds: “The client was hesitant about the elevator. Now I wish I had insisted. It would have been good for everyone.” Certainly, the exhausting climb to the top reveals a stunning view over the Palm, a rare vantage point over the endless rows of fronds and villas.

Raed adds that the view of the mosque from Atlantis is equally spectacular. He also reveals that the initial plans featured a clinic and shopping centre that “would have been in keeping with the mosque design.” The main entrance to the mosque is situated next to a large paved area. Up close, the cubist geometries recall IM Pei’s Museum of Islamic Art.

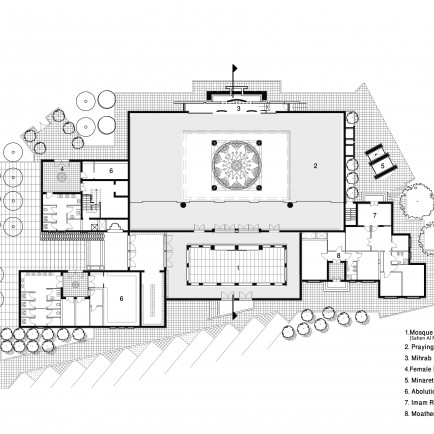

Unfortunately, a fire escape ladder mars the clean rhythm of the facade. “The fire department insisted on putting the ladder there. We wanted to place it at the back,” says Raed, understandably frustrated. The complex also contains a separate entrance for the Imam, as well as a permanent residence for the Imam and the Muezzin - the person that leads the call to prayer. “These are all requirements,” adds Raed.

The paving functions as an external prayer area, for overspill on busy times such as Fridays. “Each individual stone is aligned with Makkah and is the right dimension for a prayer mat,” adds Raed. Just like the exterior, the interior of the mosque is clean and calm, while the same patterns on the glass facade are visible on the wooden door and the window grilles. Raed remarks: “The pattern is inspired by plants images of humans and animals are forbidden in Islam.” The prayer area can accommodate 800 people, while 200 ladies can fit into the mezzanine level, concealed by a mashrabiya screen. “The ladies have to have visual and hearing contact with the Imam.

The mezzanine concept is not common in the Gulf region - usually the women are accommodated on the side,” Raed remarks. He adds that mosque designers face the dual challenges of adapting to the constraints of the site, as well as aligning the building to facing the Qibla in Makkah. Regarding the rectangular space of the space he remarks: “The designers of mosques prefer more width than length to accommodate the worshippers.”

Unlike many mosques, the interior is devoid of Islamic text, aside from the Shahada (the Muslim declaration) inscribed above the entrance. Indirect light filters in from the 20m-high dome, as well as through the facade with the stone and glass skin. “The spiritual character is apparent in the indirect natural light infiltrated in the facade,” adds Farouk. The spirituality is enhanced by the stripped-down approach. “It’s completely different to the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi. We wanted to keep things simple. The simplicity is in keeping with the teachings of Islam,” says Raed. He explains that all building services, aside from contracting, were undertaken by Yaghmour. “No other consultant was used. We did everything - structures, MEP, interiors.

We took care of every detail, we designed everything inside and out, even the shelves for the Qurans, the mashrabiya for the ladies and the shelves for the shoes by the entrance.” According to Raed, the mosque is very busy on a Friday and during Ramadan. “The initial design was for 1,500 people and there was more provision for parking,” he comments. Regarding the changes, Farouk says: “I’m satisfied with it.

The main concept is still there, with the spiritual character and indirect filtered light.” Raed says that initially the mosque raised eyebrows due to the break from the tradition approach. “At the start, the concept was difficult for people to accept. However, the Ministry of Religious Affairs likes it now.”

Farouk adds that the support of Nakheel was crucial. “Now people visit it and it has made a story and a statement. We have a movement for contemporary mosques in Jordan. I’m sure this mosque will start a movement in the UAE and the Gulf.” He points out that modern mosques are cheaper than traditional ones. “There is nothing wrong with the traditional approach but they very costly. Contemporary is easier to manufacture. Traditional requires highly skilled labour, which is getting less and less.” Farouk also believes that modern mosques are more “honest”. He continues: “It is not just change for the sake of change. It tells a story for the next generation. If we keep copying previous times, then we will not know who built what. It is more honest to express your generation and be in keeping with the times.”

Details

Location

Al Mirziban - Dubai - United Arab Emirates

Worshippers

1500

Owners

Nakheel Investment Co. Dubai

Architect Name

Year of Build

2009- 2011

Area

1500 sqm

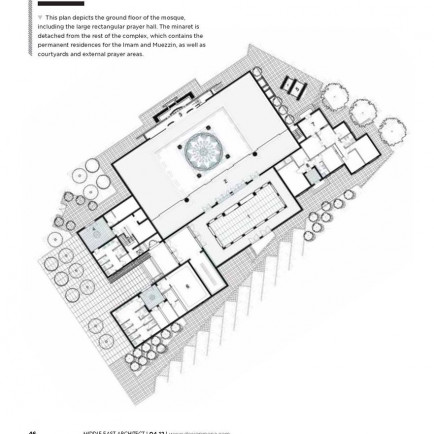

Drawings

Map

History

Located next to the tunnel for the guargantuan Atlantis hotel, the Spine Mosque on Palm Jumeirah is the polar opposite of Dubai’s famous leisure resort. Rather than mimicking Atlantis’ overwhelming exuberance, Jordan based firm “Yaghmour Architects” has designed a building that exudes simplicity, elegance and calm. Indeed, the clean-lined cubist form represents the first contemporary mosque in the UAE, a far cry from the traditionalist designs of Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi and Jumeirah Mosque in Dubai. Standing outside the entrance, Raed Yaghmour, managing director, explains how the project came about. “We were asked by Nakheel to develop an iconic mosque on Palm Jumeirah. It was the first mosque built by Nakheel. It’s a different concept for mosques as it is modern.

Urban and Architectural

Description

We thought outside of the box.” Raed adds that the benefactor was Dawalet Siddik, who honoured her father Abdulrahman. “The official name is Abdulrahman Siddik Mosque, although we sometimes refer to it as the Spine Mosque. Nakheel shared the burden with the benefactor by providing the land and half the cost of the mosque. The total budget was AED22m, excluding the land cost, and it took around two years to construct.” Farouk Yaghmour, principal in charge, who personally oversaw the design development of the building, remarks: “Nakheel called us and said there was a limited competition to design the Spine Mosque, but we didn’t know much. We have previous mosque experience in Jordan, but mosques are not necessarily our speciality. In the beginning we started with traditional designs.

With this project we tried to AED22M TOTAL budget of the SPINE MOSQUE do a different approach and transform the typology.” He continues: “The Spine Mosque was one of the first chances to go for a different approach. We wanted to use bold, contemporary materials and we were very careful in our selection of materials and how they were put together. The rough wall contrasts with the glass.” The Spine Mosque was won after Yaghmour worked with Nakheel in 2008 on an unrealized mosque in Port Rashid. “Our first mosque design for Nakheel went to the extreme of contemporary,” adds Farouk. “We designed different alternatives with a very pure glass skin.

Symbolically we included the dome and the minaret in the Spine Mosque. There was no dome in the Port Rashid Mosque.” Externally, the dominant features of the Spine Mosque are the two traditional elements - the dome and a 49m-high minaret. Yet what makes the mosque really stand out is the treatment of the facade that faces the Qibla in Makkah; with its layers of rough stone and patterned glass, it appears that the building’s skin has been sliced. Raed comments: “The glass has a double skin all the way to the ground with an insert of aluminum sheet.

Glass panels measure 2.5m by 2.5m and each unit contains four panels, so a unit measures 5m by 5m. A layer of stone emphasizes the area for the Imam - the person that leads worship in the mosque. “We wanted it to be as natural as possible so every pieced was sized. We had a hard time putting it together as it was like a jigsaw puzzle. There is a concrete structure behind and then it was glued on top.” As well as containing a rough wall, the majority of the building is clad in a smooth beige stone. Raed reveals that the rough and smooth portions are the same Omani marble. The smooth portion is also comprised of different sized blocks and this irregularity lends a handmade quality rather than a harsh uniform aesthetic. At 49m high, the minaret soars over the surrounding area. Raed remarks that the placement of the minaret was moved following a reduction in the plot size.

“With the minaret we did not have much land to work with. The plot was reduced so we had to place the minaret in a different position. The crescent on the minaret lights up at night to signify the evening call to prayer. It can be seen from a long distance.” He adds that the initial plan included an elevator to access a viewing gallery at the top of the minaret. “The viewing gallery would have been a good thing for people to come and see.

It would have meant that the building would be used not just for prayer. Now the minaret is just a monument connecting the mosque,” he remarks. Farouk adds: “The client was hesitant about the elevator. Now I wish I had insisted. It would have been good for everyone.” Certainly, the exhausting climb to the top reveals a stunning view over the Palm, a rare vantage point over the endless rows of fronds and villas.

Raed adds that the view of the mosque from Atlantis is equally spectacular. He also reveals that the initial plans featured a clinic and shopping centre that “would have been in keeping with the mosque design.” The main entrance to the mosque is situated next to a large paved area. Up close, the cubist geometries recall IM Pei’s Museum of Islamic Art.

Unfortunately, a fire escape ladder mars the clean rhythm of the facade. “The fire department insisted on putting the ladder there. We wanted to place it at the back,” says Raed, understandably frustrated. The complex also contains a separate entrance for the Imam, as well as a permanent residence for the Imam and the Muezzin - the person that leads the call to prayer. “These are all requirements,” adds Raed.

The paving functions as an external prayer area, for overspill on busy times such as Fridays. “Each individual stone is aligned with Makkah and is the right dimension for a prayer mat,” adds Raed. Just like the exterior, the interior of the mosque is clean and calm, while the same patterns on the glass facade are visible on the wooden door and the window grilles. Raed remarks: “The pattern is inspired by plants images of humans and animals are forbidden in Islam.” The prayer area can accommodate 800 people, while 200 ladies can fit into the mezzanine level, concealed by a mashrabiya screen. “The ladies have to have visual and hearing contact with the Imam.

The mezzanine concept is not common in the Gulf region - usually the women are accommodated on the side,” Raed remarks. He adds that mosque designers face the dual challenges of adapting to the constraints of the site, as well as aligning the building to facing the Qibla in Makkah. Regarding the rectangular space of the space he remarks: “The designers of mosques prefer more width than length to accommodate the worshippers.”

Unlike many mosques, the interior is devoid of Islamic text, aside from the Shahada (the Muslim declaration) inscribed above the entrance. Indirect light filters in from the 20m-high dome, as well as through the facade with the stone and glass skin. “The spiritual character is apparent in the indirect natural light infiltrated in the facade,” adds Farouk. The spirituality is enhanced by the stripped-down approach. “It’s completely different to the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi. We wanted to keep things simple. The simplicity is in keeping with the teachings of Islam,” says Raed. He explains that all building services, aside from contracting, were undertaken by Yaghmour. “No other consultant was used. We did everything - structures, MEP, interiors.

We took care of every detail, we designed everything inside and out, even the shelves for the Qurans, the mashrabiya for the ladies and the shelves for the shoes by the entrance.” According to Raed, the mosque is very busy on a Friday and during Ramadan. “The initial design was for 1,500 people and there was more provision for parking,” he comments. Regarding the changes, Farouk says: “I’m satisfied with it.

The main concept is still there, with the spiritual character and indirect filtered light.” Raed says that initially the mosque raised eyebrows due to the break from the tradition approach. “At the start, the concept was difficult for people to accept. However, the Ministry of Religious Affairs likes it now.”

Farouk adds that the support of Nakheel was crucial. “Now people visit it and it has made a story and a statement. We have a movement for contemporary mosques in Jordan. I’m sure this mosque will start a movement in the UAE and the Gulf.” He points out that modern mosques are cheaper than traditional ones. “There is nothing wrong with the traditional approach but they very costly. Contemporary is easier to manufacture. Traditional requires highly skilled labour, which is getting less and less.” Farouk also believes that modern mosques are more “honest”. He continues: “It is not just change for the sake of change. It tells a story for the next generation. If we keep copying previous times, then we will not know who built what. It is more honest to express your generation and be in keeping with the times.”