Merapi Mosque

History

After being almost completely destroyed in a volcanic eruption in

2010, the village of Kopeng in Indonesia had to be totally rebuilt – including

its mosque. While funded by a corporate bank and designed by the largest

commercial architecture practice in Indonesia, the design is a modest but

intelligent response to local conditions and the need to provide both a

religious and social focus in the village. Nicely balancing its contemporary

form and use of materials with references to traditional models, in a nicely

redemptive gesture, the Mosque also reuses the volcanic ash left by the

eruption to form the bricks of its façade. Setiadi Sopandi and Robin

Hartanto report in the second of three Buildings of the Week from Indonesia,

part of the exhibition Tropicality Revisited: Recent Approaches by

Indonesian Architects, on show at the DAM/Deutsches Architekturmuseum in

Frankfurt until January 3, 2016.

The Baiturrahman Mosque is located at Kopeng Village, in the

district of Sleman, north of Yogyakarta in Indonesia. Situated on the southern

slope of Merapi volcano, the village – one of several surrounding the peak of

Merapi – is only seven kilometres away from the peak. Merapi is one of the most

active volcanoes in the region, and has had at least two major eruptions since

2000. During the last in 2010, the alert was raised to the highest level in

October, and everyone living within ten kilometres radius were first warned and

then evacuated. However, by the end of December, there was approximately

320,000 people displaced and at least 353 people reported dead, most killed by

severe burns from hot ash clouds – known locally as wedhus gembel.

By mid-2011, when the emergency receded, villagers gradually came

back to rebuild their houses and their livelihoods. Most of their properties –

including precious livestock and farms – were burnt, leaving only bricks,

stones, and a few hardwood elements to be reused.

Many organisations and companies helped the villagers rebuild

their houses as well as their community facilities. Bank Muamalat – one of the

largest Islamic banking corporations in the country – took the initiative to

build a community mosque for Kopeng Village as part of its corporate social

responsibility scheme. Baitulmaal Muamalat, the company’s charitable

foundation, commissioned the commercial architects Urbane Indonesia to come up

with a concept for the mosque.

The firm came up with the idea of a “modern-looking” mosque of

simple reinforced concrete construction but dressed with local unfired bricks

made from the abundant volcanic ash. The structure, located at a corner on a

T-junction in the village, is a relatively small one, at only 250 square metres

gross floor area, compared to the scale of the practice’s usual commissions.

However, Urbane Indonesia’s previous design for a community

mosque, the Al-Irsyad Mosque, completed in April 2010 in the Padalarang area of

the city Bandung, provided a precedent being a hollow box cladded in an

elaborate composition of fabricated concrete blocks.

Similarly the Baiturrahman Mosque has a box-like aesthetic, but

here the concrete block composition was developed not only as an aesthetic

feature but also as a means to light, and (at least initially) to ventilate the

interior. Additionally, the use of volcanic ash to construct bricks was an

intelligent use of a locally abundant material.

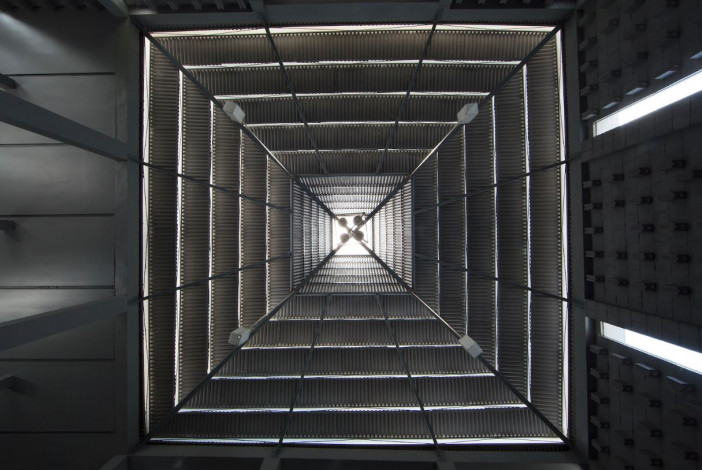

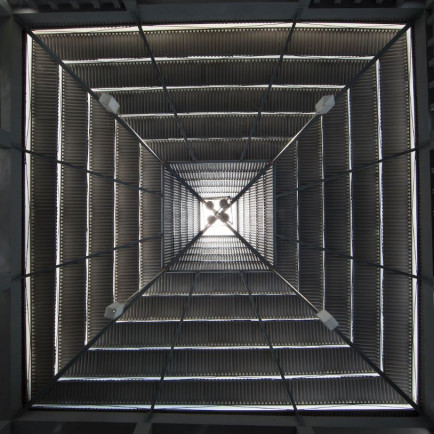

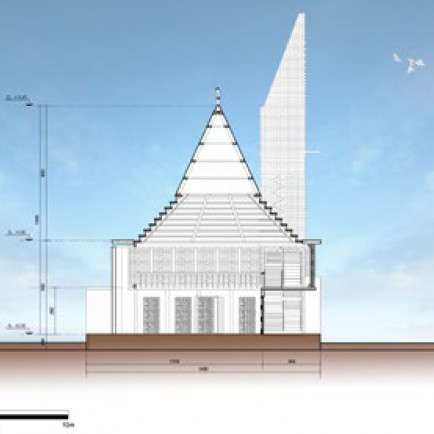

While liking the ash brick idea, Bank Muamalat initially felt uneasy with the idea of a dome-less mosque, fearing that it might be rejected by the villagers. The architect subsequently proposed an interpretation of the vernacular Indonesian stacked pendopo roof, here made of metal sheet panels rather than traditional timber and tiles: an idea which was presented to the Kopeng villagers in August 2011 and won their approval. Each layer of the stacked roof leaves an opening slit which creates a nice play of light visible from the interior, although the lighting effect could have been more dramatic had the initial design of a much steeper and more elaborate roof form been adopted.

Urban and Architectural

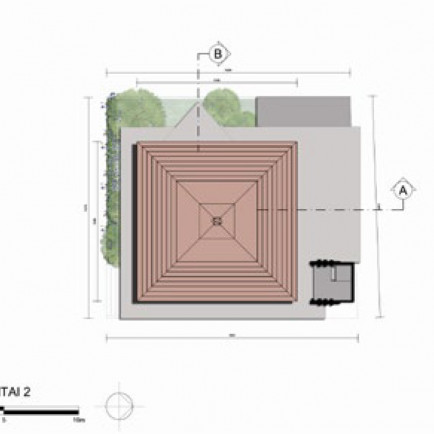

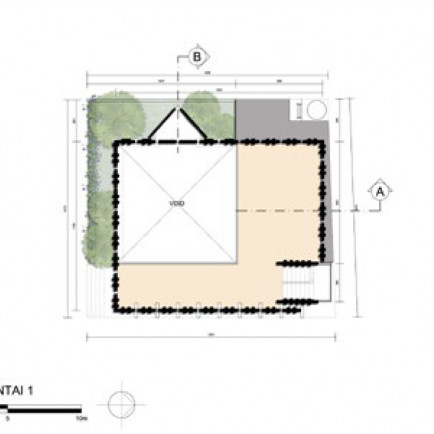

The simple layout of the mosque consists of a main prayer hall

surrounded by a verandah, around which are the ablution chambers, toilets and a

staircase to the mezzanine level and the tower. It is intended that the mosque

should not only to be a place for prayers but also a community centre for

children and a watchtower for the village.

The overall form of the mosque is a striking contrast to the

surrounding buildings. The soaring tower appears to dominate the landscape of

dusty roads and the greyish roof tiles of villagers’ houses. Kamil developed

the design by emphasising the composition of small openings, formed by

placing the volcanic ash bricks at different angles over the façades. With the

main entrance facing East, the interior is lit with a pleasant lighting effect

from the morning and evolves throughout the day.

While the architect was deliberately aiming to free up the image

of a mosque away from the automatic presence of a dome, he was following the

tradition of a mosque as an open, shed-like structure. Early mosques in

Indonesia took their forms from vernacular traditions: timber structures

supporting elaborate roof forms – often multitiered – without walls and devoid

of furniture. Such structures provided good protection against both heavy rain

and heat from the sun, while allowing for breezes to pass through.

Modern mosques also continue in these traditions: prayer halls are

often well-shaded, well-ventilated and spacious. As a result, mosques often

provide pleasant spaces for social gatherings or simply as places to sit on the

floor or take a nap during the hot early afternoons. This quality appears even

in the grandest mosque in Indonesia, the Istiqlal, designed by F. Silaban in

the 1950s and completed in the late 1970s. Silaban designed the Istiqlal as an

enormous shed supported by rows of tall monumental columns clad with layers of

marble. Despite the monumental formality expressed by the architecture’s scale

and proportion, the shaded verandahs of the design enables many informal

activities to take place around it. Such an arrangement is also apparent

further afield in many other mosques found in tropical climates, such as those

of the Mughal Dynasty in northern India, where summers are unforgivingly hot.

At the Baiturrahman, also located in a hot humid region, the

openings were also meant to allow breezes to penetrate the interior. However,

as it is located high on the mountainside, the surrounding temperature can drop

to as low as 16°C which causes the interior to become unpleasantly cold because

of the chill winds coming down from the mountain. Additionally, the residual

volcanic ash in the area and the growth of the volcanic sand mining industry

have begun to cause heavy pollution in the interior. As the result, the

openings have been sealed with glass.

The finished building is

less elaborate than the original design – the tower in particular is much

simpler than was planned – and aside from the addition of the glass, a stretch

of awning roof has also been added by local residents to protect the verandah

from splattering rain. But while the original design, developed from a set of

preconceived ideas proposed by the architect to the funding sponsor, has since

been adapted to the climatic context and specific needs of its users, the

overall aesthetic quality – of strong graphic simplicity – has not been

compromised.

Description

Details

Location

Yogyakarta City, Special Region of Yogyakarta 55166, Indonesia

Worshippers

208

Architect Name

Year of Build

2011

Area

250 SQM

Drawings

Map

History

After being almost completely destroyed in a volcanic eruption in

2010, the village of Kopeng in Indonesia had to be totally rebuilt – including

its mosque. While funded by a corporate bank and designed by the largest

commercial architecture practice in Indonesia, the design is a modest but

intelligent response to local conditions and the need to provide both a

religious and social focus in the village. Nicely balancing its contemporary

form and use of materials with references to traditional models, in a nicely

redemptive gesture, the Mosque also reuses the volcanic ash left by the

eruption to form the bricks of its façade. Setiadi Sopandi and Robin

Hartanto report in the second of three Buildings of the Week from Indonesia,

part of the exhibition Tropicality Revisited: Recent Approaches by

Indonesian Architects, on show at the DAM/Deutsches Architekturmuseum in

Frankfurt until January 3, 2016.

The Baiturrahman Mosque is located at Kopeng Village, in the

district of Sleman, north of Yogyakarta in Indonesia. Situated on the southern

slope of Merapi volcano, the village – one of several surrounding the peak of

Merapi – is only seven kilometres away from the peak. Merapi is one of the most

active volcanoes in the region, and has had at least two major eruptions since

2000. During the last in 2010, the alert was raised to the highest level in

October, and everyone living within ten kilometres radius were first warned and

then evacuated. However, by the end of December, there was approximately

320,000 people displaced and at least 353 people reported dead, most killed by

severe burns from hot ash clouds – known locally as wedhus gembel.

By mid-2011, when the emergency receded, villagers gradually came

back to rebuild their houses and their livelihoods. Most of their properties –

including precious livestock and farms – were burnt, leaving only bricks,

stones, and a few hardwood elements to be reused.

Many organisations and companies helped the villagers rebuild

their houses as well as their community facilities. Bank Muamalat – one of the

largest Islamic banking corporations in the country – took the initiative to

build a community mosque for Kopeng Village as part of its corporate social

responsibility scheme. Baitulmaal Muamalat, the company’s charitable

foundation, commissioned the commercial architects Urbane Indonesia to come up

with a concept for the mosque.

The firm came up with the idea of a “modern-looking” mosque of

simple reinforced concrete construction but dressed with local unfired bricks

made from the abundant volcanic ash. The structure, located at a corner on a

T-junction in the village, is a relatively small one, at only 250 square metres

gross floor area, compared to the scale of the practice’s usual commissions.

However, Urbane Indonesia’s previous design for a community

mosque, the Al-Irsyad Mosque, completed in April 2010 in the Padalarang area of

the city Bandung, provided a precedent being a hollow box cladded in an

elaborate composition of fabricated concrete blocks.

Similarly the Baiturrahman Mosque has a box-like aesthetic, but

here the concrete block composition was developed not only as an aesthetic

feature but also as a means to light, and (at least initially) to ventilate the

interior. Additionally, the use of volcanic ash to construct bricks was an

intelligent use of a locally abundant material.

While liking the ash brick idea, Bank Muamalat initially felt uneasy with the idea of a dome-less mosque, fearing that it might be rejected by the villagers. The architect subsequently proposed an interpretation of the vernacular Indonesian stacked pendopo roof, here made of metal sheet panels rather than traditional timber and tiles: an idea which was presented to the Kopeng villagers in August 2011 and won their approval. Each layer of the stacked roof leaves an opening slit which creates a nice play of light visible from the interior, although the lighting effect could have been more dramatic had the initial design of a much steeper and more elaborate roof form been adopted.

Urban and Architectural

The simple layout of the mosque consists of a main prayer hall

surrounded by a verandah, around which are the ablution chambers, toilets and a

staircase to the mezzanine level and the tower. It is intended that the mosque

should not only to be a place for prayers but also a community centre for

children and a watchtower for the village.

The overall form of the mosque is a striking contrast to the

surrounding buildings. The soaring tower appears to dominate the landscape of

dusty roads and the greyish roof tiles of villagers’ houses. Kamil developed

the design by emphasising the composition of small openings, formed by

placing the volcanic ash bricks at different angles over the façades. With the

main entrance facing East, the interior is lit with a pleasant lighting effect

from the morning and evolves throughout the day.

While the architect was deliberately aiming to free up the image

of a mosque away from the automatic presence of a dome, he was following the

tradition of a mosque as an open, shed-like structure. Early mosques in

Indonesia took their forms from vernacular traditions: timber structures

supporting elaborate roof forms – often multitiered – without walls and devoid

of furniture. Such structures provided good protection against both heavy rain

and heat from the sun, while allowing for breezes to pass through.

Modern mosques also continue in these traditions: prayer halls are

often well-shaded, well-ventilated and spacious. As a result, mosques often

provide pleasant spaces for social gatherings or simply as places to sit on the

floor or take a nap during the hot early afternoons. This quality appears even

in the grandest mosque in Indonesia, the Istiqlal, designed by F. Silaban in

the 1950s and completed in the late 1970s. Silaban designed the Istiqlal as an

enormous shed supported by rows of tall monumental columns clad with layers of

marble. Despite the monumental formality expressed by the architecture’s scale

and proportion, the shaded verandahs of the design enables many informal

activities to take place around it. Such an arrangement is also apparent

further afield in many other mosques found in tropical climates, such as those

of the Mughal Dynasty in northern India, where summers are unforgivingly hot.

At the Baiturrahman, also located in a hot humid region, the

openings were also meant to allow breezes to penetrate the interior. However,

as it is located high on the mountainside, the surrounding temperature can drop

to as low as 16°C which causes the interior to become unpleasantly cold because

of the chill winds coming down from the mountain. Additionally, the residual

volcanic ash in the area and the growth of the volcanic sand mining industry

have begun to cause heavy pollution in the interior. As the result, the

openings have been sealed with glass.

The finished building is

less elaborate than the original design – the tower in particular is much

simpler than was planned – and aside from the addition of the glass, a stretch

of awning roof has also been added by local residents to protect the verandah

from splattering rain. But while the original design, developed from a set of

preconceived ideas proposed by the architect to the funding sponsor, has since

been adapted to the climatic context and specific needs of its users, the

overall aesthetic quality – of strong graphic simplicity – has not been

compromised.

Description