Al-jadid Mosque (New Mosque) of Algiers

History

The congregational mosque Jami' al-Jadid, also called the Mosque of the Fishery, is situated in Algiers, the capital of contemporary Algeria. The mosque's main entrance doorway has an inscription over it that dates it to 1660/1070 AH. Al-Hajj Habib, a Janissary ruler of the Algiers province chosen by the Ottoman imperial authority in Istanbul, is also credited with building the inscription. Although the mosque's setting inside a North African culture still has an undercurrent impact on the building, Ottoman patronage drives the edifice in terms of both planning and ornamentation. The structure is distinctive for its fusion of many architectural styles, including aspects of Andalusian and Italian ecclesiastical architecture that were popular at the time in north Africa.

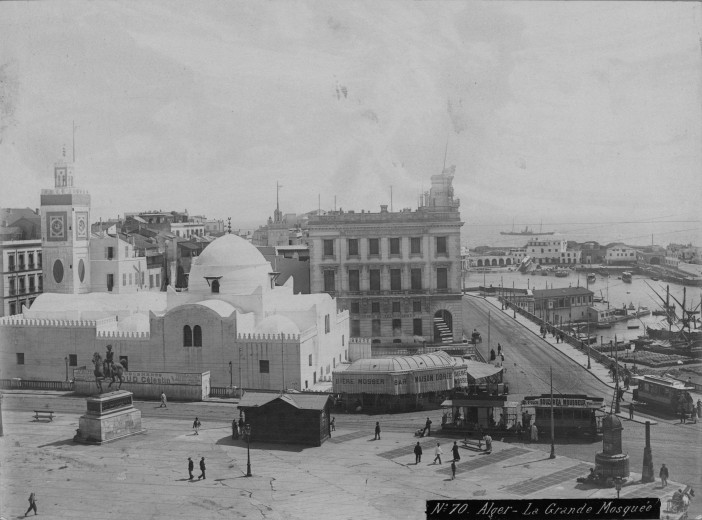

The Mosque of the Fishery, with its qibla wall abutting the northern side of Boulevard Amilcar Cabral, marks the eastern border of the Place des Martyrs. In addition to the Mosque of the Fishery, the Almoravid Grand Mosque of Algiers is located on the boulevard 70 meters to the east of it. The road along the Algiers harbor is formed by a drop in the ground just southeast of the roadway. Due to its close proximity to the waterfront and frequentation by local fisherman, the mosque acquired its informal appellation. The Almohad qasba, which was substantially destroyed during the French colonization of Algeria in the late eighteenth century, once extended to the southernmost point of the city where the mosque is now situated.

The outside of the Mosque of the Fishery's stone construction has been entirely whitewashed, including the domes and roof vaults, giving it a neat, uniform aspect. A narrow strip of tile work that trims the ornate merlons running along the top of the mosque's perimeter walls facing the street and the Place des Martyrs is one of the only splashes of color on the otherwise monochromatic facade. A delicate metal finial made of four stacked spheres sits atop the building's central dome and is another aesthetic feature on the exterior.

Though the Mosque of the Fishery's design and ornamentation clearly show an Ottoman influence, it's odd that the mosque's minaret is largely based on traditional North African forms. Due to the street level gradually rising, the minaret now rises 25 meters above the Place des Martyrs from its original height of 30 meters. The square-shaped minaret has a straight shaft that connects its three internal floors with a small, enclosed stairway. The whitewashed stone building's two top floors have decorative panels inserted into them; on the second level, rectangular inset panels enclose ovals made of patterned tile, and on the third level, clock faces with rectangular tiled frames surround them on all four elevations. The clock, which Bournichon incorporated into the minaret, was originally a component of the Palais Jénina. A large tiled cornice around all four elevations highlights the balcony above the third floor, which is bordered by pyramidal merlons. A small square pavilion with a domed roof and a finial made of three metal spheres is surrounded by the balcony and has a trim of little merlons. The pavilion has doubled arched openings, a central oculus, and perforations on all four sides. It is an open structure.

Urban and Architectural

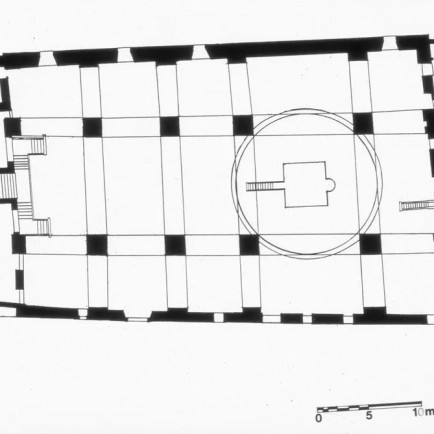

The mosque's floor design is forty-eight meters long and twenty-seven meters broad from north to south. The qibla wall forms the southern boundary of the structure, and its longitudinal axis is tilted twenty degrees away from the meridian running north to south.

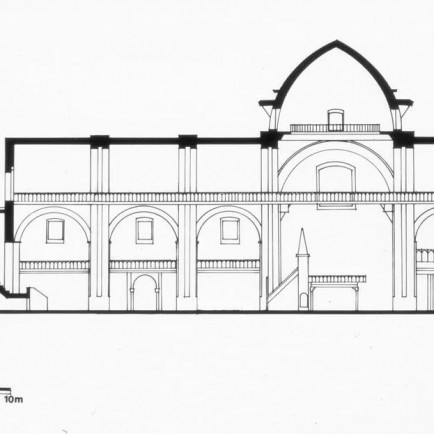

The square mosque is irregularly divided into a grid that is three aisles wide and five bays deep, with the exception of a sixth bay of chambers that flank the main stairway that descends into the mosque. The steps were constructed as the street level increased; at this time, the mosque's interior ground level is five meters below street level. The interior of the building is divided into eight sections by eight substantial stone piers, each two meters square in plan. The central aisle's cloister-vaulted ceiling and the side aisles' gored domes are supported by round arches that are affixed to the tops of the piers. The central vault that the round arches support rises to a height of just over fourteen meters, while the round arches themselves rise to a height of nine meters above the floor at their centers. In comparison to the other five-meter-wide aisles and bays, the center aisle and the fourth bay are significantly broader, spanning nine and a half meters between the piers. The layout is given a cruciform shape by their enlarged size, evoking previous Ottoman mosque designs from the seventeenth century, which frequently feature sizable domes at the intersection of perpendicular axes.

An eight-meter-tall pointed dome rising from pendentives and a drum with a diameter of around ten meters serve as the intersection's top features. The dome's core rises up to a maximum height of 23 meters. The tympana of the blind arches along the outer walls and the drum of the dome both have windows. As is typical of Ottoman mosques, the mihrab and marble minbar are situated right beneath the main dome. A large hypostyle prayer hall in North Africa often has a T-shaped layout instead of the quatrefoil or octagonal Ottoman layouts, with the minbar placed along the qibla wall at one end. The plan of the Mosque of the Fishery, however, departs in at least two important ways from that of traditional quatrefoil Ottoman mosques, such as Sinan's Sehzade Mehmed Mosque (1544-1549 CE / AH 951-956). In the Algerian example, the Ottoman model's supporting domes that abut the central dome on all four sides were swapped out for vaulted ceilings on the two opposing sides, and one of those vaulted aisles was further extended by two bays to produce an asymmetry within the prayer hall's plan that resembles the nave of a European church. With this action, the area that typically serves as an outer forecourt in mosques like the aforementioned Sehzade Mehmed is effectively enclosed.

Description

The interior ornamentation of the building maintains the jumble of architectural traditions; the ornate carvings on the minbar clearly show Italian influences, yet the large horseshoe arch of the mihrab is based on Andalusian models. Although the minbar's components are all typical of North African minbars, Ottoman tastes may be seen in the use of Italian marble in place of wood.

Some academics have proposed that the Mosque of the Fishery's distinctiveness may be linked to its designer's lack of acquaintance with specific Ottoman architectural traditions as a result of Algiers' actual removal from Istanbul, the location of the empire's capital. The peculiar mosque is a result of a strong blending of Ottoman, North African, and southern European traditions, which may have been influenced by the physical and cultural distance. However, in contrast to the numerous other mosques in the city that faithfully adhered to North African building traditions, the mosque would have unquestionably appeared Ottoman to its contemporaries in seventeenth-century Algiers.

Details

Location

Q3M7+X6R Djemaa El Djedid, Boulevard Amilcar Cabral, Algiers, Algeria

Worshippers

650

Owners

al-Hajj Habib

Architect Name

Year of Build

1660

Area

1296

Drawings

Map

History

The congregational mosque Jami' al-Jadid, also called the Mosque of the Fishery, is situated in Algiers, the capital of contemporary Algeria. The mosque's main entrance doorway has an inscription over it that dates it to 1660/1070 AH. Al-Hajj Habib, a Janissary ruler of the Algiers province chosen by the Ottoman imperial authority in Istanbul, is also credited with building the inscription. Although the mosque's setting inside a North African culture still has an undercurrent impact on the building, Ottoman patronage drives the edifice in terms of both planning and ornamentation. The structure is distinctive for its fusion of many architectural styles, including aspects of Andalusian and Italian ecclesiastical architecture that were popular at the time in north Africa.

The Mosque of the Fishery, with its qibla wall abutting the northern side of Boulevard Amilcar Cabral, marks the eastern border of the Place des Martyrs. In addition to the Mosque of the Fishery, the Almoravid Grand Mosque of Algiers is located on the boulevard 70 meters to the east of it. The road along the Algiers harbor is formed by a drop in the ground just southeast of the roadway. Due to its close proximity to the waterfront and frequentation by local fisherman, the mosque acquired its informal appellation. The Almohad qasba, which was substantially destroyed during the French colonization of Algeria in the late eighteenth century, once extended to the southernmost point of the city where the mosque is now situated.

The outside of the Mosque of the Fishery's stone construction has been entirely whitewashed, including the domes and roof vaults, giving it a neat, uniform aspect. A narrow strip of tile work that trims the ornate merlons running along the top of the mosque's perimeter walls facing the street and the Place des Martyrs is one of the only splashes of color on the otherwise monochromatic facade. A delicate metal finial made of four stacked spheres sits atop the building's central dome and is another aesthetic feature on the exterior.

Though the Mosque of the Fishery's design and ornamentation clearly show an Ottoman influence, it's odd that the mosque's minaret is largely based on traditional North African forms. Due to the street level gradually rising, the minaret now rises 25 meters above the Place des Martyrs from its original height of 30 meters. The square-shaped minaret has a straight shaft that connects its three internal floors with a small, enclosed stairway. The whitewashed stone building's two top floors have decorative panels inserted into them; on the second level, rectangular inset panels enclose ovals made of patterned tile, and on the third level, clock faces with rectangular tiled frames surround them on all four elevations. The clock, which Bournichon incorporated into the minaret, was originally a component of the Palais Jénina. A large tiled cornice around all four elevations highlights the balcony above the third floor, which is bordered by pyramidal merlons. A small square pavilion with a domed roof and a finial made of three metal spheres is surrounded by the balcony and has a trim of little merlons. The pavilion has doubled arched openings, a central oculus, and perforations on all four sides. It is an open structure.

Urban and Architectural

The mosque's floor design is forty-eight meters long and twenty-seven meters broad from north to south. The qibla wall forms the southern boundary of the structure, and its longitudinal axis is tilted twenty degrees away from the meridian running north to south.

The square mosque is irregularly divided into a grid that is three aisles wide and five bays deep, with the exception of a sixth bay of chambers that flank the main stairway that descends into the mosque. The steps were constructed as the street level increased; at this time, the mosque's interior ground level is five meters below street level. The interior of the building is divided into eight sections by eight substantial stone piers, each two meters square in plan. The central aisle's cloister-vaulted ceiling and the side aisles' gored domes are supported by round arches that are affixed to the tops of the piers. The central vault that the round arches support rises to a height of just over fourteen meters, while the round arches themselves rise to a height of nine meters above the floor at their centers. In comparison to the other five-meter-wide aisles and bays, the center aisle and the fourth bay are significantly broader, spanning nine and a half meters between the piers. The layout is given a cruciform shape by their enlarged size, evoking previous Ottoman mosque designs from the seventeenth century, which frequently feature sizable domes at the intersection of perpendicular axes.

An eight-meter-tall pointed dome rising from pendentives and a drum with a diameter of around ten meters serve as the intersection's top features. The dome's core rises up to a maximum height of 23 meters. The tympana of the blind arches along the outer walls and the drum of the dome both have windows. As is typical of Ottoman mosques, the mihrab and marble minbar are situated right beneath the main dome. A large hypostyle prayer hall in North Africa often has a T-shaped layout instead of the quatrefoil or octagonal Ottoman layouts, with the minbar placed along the qibla wall at one end. The plan of the Mosque of the Fishery, however, departs in at least two important ways from that of traditional quatrefoil Ottoman mosques, such as Sinan's Sehzade Mehmed Mosque (1544-1549 CE / AH 951-956). In the Algerian example, the Ottoman model's supporting domes that abut the central dome on all four sides were swapped out for vaulted ceilings on the two opposing sides, and one of those vaulted aisles was further extended by two bays to produce an asymmetry within the prayer hall's plan that resembles the nave of a European church. With this action, the area that typically serves as an outer forecourt in mosques like the aforementioned Sehzade Mehmed is effectively enclosed.

Description

The interior ornamentation of the building maintains the jumble of architectural traditions; the ornate carvings on the minbar clearly show Italian influences, yet the large horseshoe arch of the mihrab is based on Andalusian models. Although the minbar's components are all typical of North African minbars, Ottoman tastes may be seen in the use of Italian marble in place of wood.

Some academics have proposed that the Mosque of the Fishery's distinctiveness may be linked to its designer's lack of acquaintance with specific Ottoman architectural traditions as a result of Algiers' actual removal from Istanbul, the location of the empire's capital. The peculiar mosque is a result of a strong blending of Ottoman, North African, and southern European traditions, which may have been influenced by the physical and cultural distance. However, in contrast to the numerous other mosques in the city that faithfully adhered to North African building traditions, the mosque would have unquestionably appeared Ottoman to its contemporaries in seventeenth-century Algiers.