Al-Salih Tala'i Mosque

History

Tala'i ibn Ruzzik, vizier of the Fatimids, gave the mosque its order in 1160. One of the last effective and powerful viziers who preserved some degree of stability in the Fatimid Empire during its latter decades was Tala'i. This mosque is the final significant Fatimid structure to have been constructed because the Fatimid Caliphate was abolished in 1171. (and which still survives). In Cairo's post-Fatimid architecture, some of the mosque's original decorative components can still be seen.

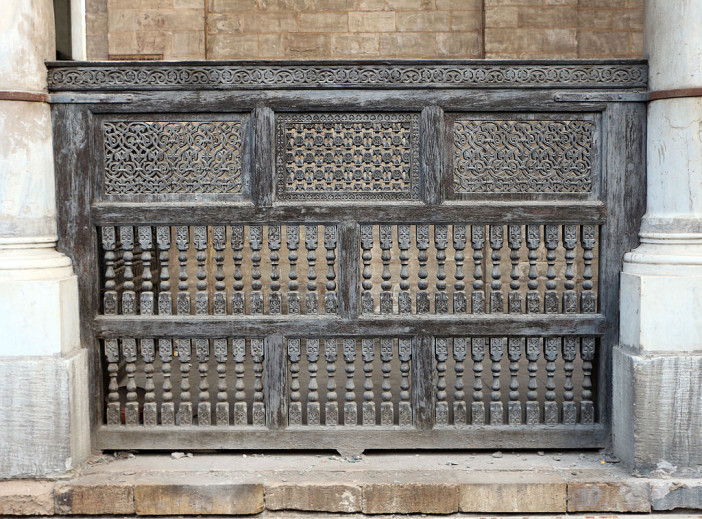

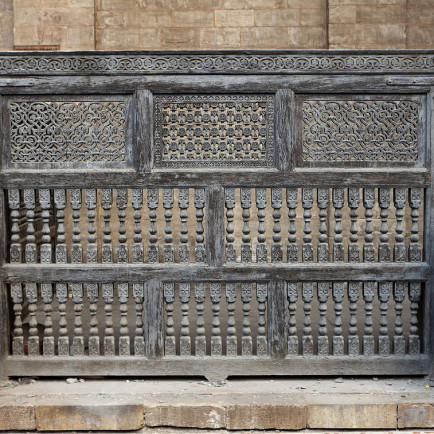

After an earthquake in 1303 demolished the minaret that stood over the mosque's front porch, the mosque was rebuilt during the Mamluk dynasty. At this period, the original main doors, which had been carved in wood, received Mamluk-style bronze facings. The original doors, which featured both the Fatimid wood-carved and Mamluk bronze-faced facades, are now shown at Cairo's Museum of Islamic Art. The portico in front of the mosque received wooden mashrabiyya screens as part of the Mamluk repair, which are still in place today. The mosque's interior minbar, which dates to the Mamluk era between 1299 and 1300 and was a gift from the Mamluk amir Baktimur al-Jugandar, is one of the oldest ones still standing in Cairo.

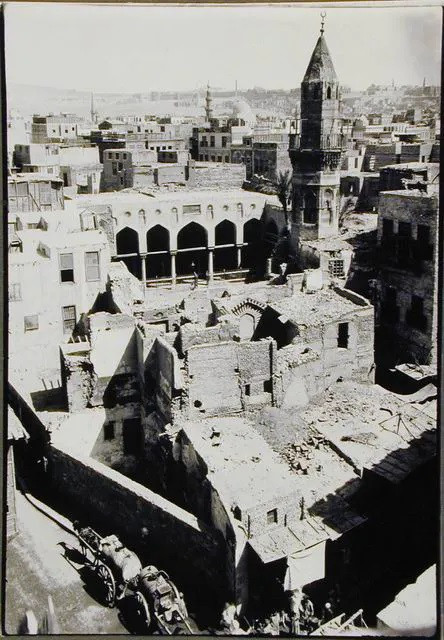

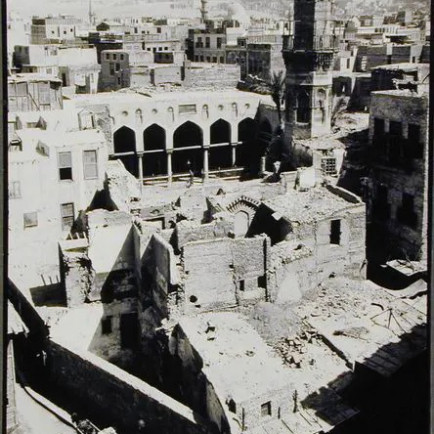

The Comité de Conservation des Monuments de l'Art Arabe significantly repaired the mosque in the early 20th century from a state of near-ruin, but much of the original structure still stands today. The mosque's base is currently about two meters below the current street level, demonstrating how much the city's street level has risen since the 12th century, along with the stores that originally lined its facade.

Urban and Architectural

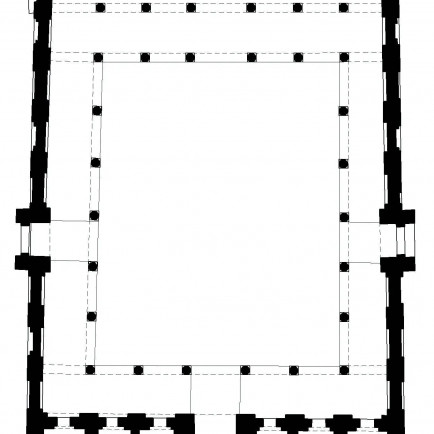

The mosque was erected on an elevated platform with built-in alcoves on three sides (all save the qibla side) that were intended to house businesses that supported the mosque financially. Thus, it was Cairo's first "hanging" mosque—that is, a mosque with a prayer area that is elevated above street level. A main entrance to the northwest and two lateral entrances on the sides make up the mosque's three entrances. The front (northwestern) entrance is flanked by a portico with five arches, a feature that was unusual in Cairo (at least before the much later Ottoman period). If the head of Husayn had been buried here as intended, the portico may have served as a royal viewing platform for processions through Bab Zuweila or for some other ceremonial purpose. One of only a few Fatimid-era ceilings of its kind that have been preserved is the original ceiling just beneath or inside the portico. The wooden doors at the mosque's entrance today are reproductions of the originals, which are now housed in the Museum of Islamic Art, as was previously mentioned. Over the mosque's entrance there used to be a minaret, but it was damaged in the 1303 earthquake. A subsequent minaret built during the Ottoman era was eventually taken down during restoration work in the 20th century. Its old location is most likely indicated by the stairs that is still visible and connects to the roof today.

Description

The interior of the mosque is divided into a courtyard and an arcade of keel-shaped arches, with the south-east (qibla) side of the mosque extending deeper to create a prayer hall three rows deep. The mosque's original design did not include the arcade on the northwest side (the side with the main entrance), which was inadvertently built during the Comité restoration in the 20th century. The inside is decorated with stucco-carved window grilles, wooden tie-beams between columns, and Kufic-style Qur'anic inscriptions on the outlines of the prayer hall's arches. The extant Kufic inscriptions in the prayer hall show a very elaborate late-Fatimid style in which the letters are carved against a background of vegetable arabesques, but much of the inscriptions around the arches have already vanished.

References

https://www.archnet.org/sites/2324

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Salih_Tala%27i_Mosque

https://earth.google.com/web/search/Mosque+of+al-Salih+Tala%27i,+El-Darb+El-Ahmar,+Egypt/@30.04206075,31.25812224,25.04817979a,253.04304026d,35y,57.58123941h,0t,0r/data=CpMBGmkSYwolMHgxNDU4NDBhNmJhMWYwZTA1OjB4NDc1MGYzNjExYzVjMDVhOCo6TW9zcXVlIG9mIGFsLVNhbGloIFRhbGEnaQrYrNin2YXYuSDYp9mE2LXYp9mE2K0g2LfZhNin2KbYuRgDIAEiJgokCWiOX-VMBj5AESQOhKQWBT5AGaR-1NA4RT9AIb7-MZQZRD9A

Details

Location

27R5+W6X Mosque of al-Salih Tala'i, El-Darb El-Ahmar, Cairo Governorate 4292233, Egypt

Worshippers

775

Owners

Al-Salih Tala'i' ibn Ruzzik

Architect Name

Year of Build

built : 1160, restored 1303

Area

1550

Drawings

Map

History

Tala'i ibn Ruzzik, vizier of the Fatimids, gave the mosque its order in 1160. One of the last effective and powerful viziers who preserved some degree of stability in the Fatimid Empire during its latter decades was Tala'i. This mosque is the final significant Fatimid structure to have been constructed because the Fatimid Caliphate was abolished in 1171. (and which still survives). In Cairo's post-Fatimid architecture, some of the mosque's original decorative components can still be seen.

After an earthquake in 1303 demolished the minaret that stood over the mosque's front porch, the mosque was rebuilt during the Mamluk dynasty. At this period, the original main doors, which had been carved in wood, received Mamluk-style bronze facings. The original doors, which featured both the Fatimid wood-carved and Mamluk bronze-faced facades, are now shown at Cairo's Museum of Islamic Art. The portico in front of the mosque received wooden mashrabiyya screens as part of the Mamluk repair, which are still in place today. The mosque's interior minbar, which dates to the Mamluk era between 1299 and 1300 and was a gift from the Mamluk amir Baktimur al-Jugandar, is one of the oldest ones still standing in Cairo.

The Comité de Conservation des Monuments de l'Art Arabe significantly repaired the mosque in the early 20th century from a state of near-ruin, but much of the original structure still stands today. The mosque's base is currently about two meters below the current street level, demonstrating how much the city's street level has risen since the 12th century, along with the stores that originally lined its facade.

Urban and Architectural

The mosque was erected on an elevated platform with built-in alcoves on three sides (all save the qibla side) that were intended to house businesses that supported the mosque financially. Thus, it was Cairo's first "hanging" mosque—that is, a mosque with a prayer area that is elevated above street level. A main entrance to the northwest and two lateral entrances on the sides make up the mosque's three entrances. The front (northwestern) entrance is flanked by a portico with five arches, a feature that was unusual in Cairo (at least before the much later Ottoman period). If the head of Husayn had been buried here as intended, the portico may have served as a royal viewing platform for processions through Bab Zuweila or for some other ceremonial purpose. One of only a few Fatimid-era ceilings of its kind that have been preserved is the original ceiling just beneath or inside the portico. The wooden doors at the mosque's entrance today are reproductions of the originals, which are now housed in the Museum of Islamic Art, as was previously mentioned. Over the mosque's entrance there used to be a minaret, but it was damaged in the 1303 earthquake. A subsequent minaret built during the Ottoman era was eventually taken down during restoration work in the 20th century. Its old location is most likely indicated by the stairs that is still visible and connects to the roof today.

Description

The interior of the mosque is divided into a courtyard and an arcade of keel-shaped arches, with the south-east (qibla) side of the mosque extending deeper to create a prayer hall three rows deep. The mosque's original design did not include the arcade on the northwest side (the side with the main entrance), which was inadvertently built during the Comité restoration in the 20th century. The inside is decorated with stucco-carved window grilles, wooden tie-beams between columns, and Kufic-style Qur'anic inscriptions on the outlines of the prayer hall's arches. The extant Kufic inscriptions in the prayer hall show a very elaborate late-Fatimid style in which the letters are carved against a background of vegetable arabesques, but much of the inscriptions around the arches have already vanished.