Bibi Khanym Mosque

History

Whatever the truth of the matter, the timing of the mosque's construction—beginning in 1399—corresponds to the year following Timur's wildly successful Delhi campaign that resulted in tremendous spoils brought back to Samarkand, carried on the backs of 95 war elephants (themselves spoils of war) which were later repurposed as heavy-duty haulers at the burgeoning construction site. Although conceived on a massive scale, Timur was in a great hurry to see the mosque finished. Clavijo notes that when Timur looked upon the completed entrance iwan he was dissatisfied with the height and ordered it torn down, executing the amirs responsible for the construction. He then personally took charge of the workmen responsible for one of two deep excavations required for the larger gate, periodically tossing them meat and gold coins to spur on their labors.Construction of the mosque ended in 1405, the same year Timur died from fever during his abortive China campaign. Already, the mosque was showing signs of instability with the dome beginning to crumble and masonry falling on worshippers. The architects, urged on by Timur's oversize ambitions, had made the structure too large to accommodate its own weight and insufficiently stable in an active seismic zone. Timur's generally weak successors, plagued by infighting, had neither the means nor the motivation to shore up the slowly collapsing building. A few made half-hearted additions without resolving the root of the problem, such as Ulugh Beg's gift of an enormous Koran stand that was once mounted in the main chamber but is now on display at the center of the courtyard. Still, its decay was a slow process and it appears to have remained in some form of active use at least through the 17th century when Yalangtush Bakhodur (a.k.a., Yalangtush Bi Alchin) finally built the Tilla Kori mosque and madrassa as a replacement. For centuries thereafter the ruinous mosque languished at the heart of Samarkand, frequently the target of thieves who were eager to repurpose its fine bricks and marble for their own purposes. By the late 19th century the slow stripping of construction material had lead to the near-disappearance of the perimeter walls and galleries.

Further tragedy struck in 1897 when an earthquake rocked Samarkand, bringing down the inner arch of the main iwan. Though still standing, the main dome was riven with cracks and the drum was in a state of near-collapse, as can be seen in the pioneering color photographs of Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii from 1905-1915

Refurbishment and restoration of the ruin began in earnest in the 1970s with Soviet conservationists first taking steps to shore up the collapsing structure. While they made some headway, the bulk of the work took place in the post-Soviet era under the rule of Uzbekistan's first president, Islam Karimov, who lavished funds on restoring Timurid-era buildings as part of a wider plan to redefine Timur as a native-born hero, the pride of all Uzbeks. To these ends, the monument had to be restored in toto so that the legacy of Timur was renewal, not a ruin

Urban and Architectural

In spite of its size, the design of the Bibi Khanum was not especially innovative. Since the 12th century the four-iwan plan mosque had predominated in Persian lands, and Timur's captive Persian artisans (relocated to Samarkand following the conquest of their homeland) would have been readily familiar with the design, which Bloom describes as a copy of the (now destroyed) mosque of the Ilkhanid sultan Uljaytu at Sultaniyya, Iran. One minor innovation was the addition of domes to the side iwans, turning each into freestanding structures. These side chambers are emblematic of the versatility of Timurid architecture: if viewed in isolation, each are identical to freestanding mausolea, showcasing that for the Timurids, function is not determined by form.The Uzbek conservationists successfully stabilized and restored the collapsing main dome, rebuilt the entrance arch broken in the 1897 earthquake, reconstructed the vanished domes on the side iwans, and everywhere replaced crumbling brick with new masonry indistinguishable from the old.

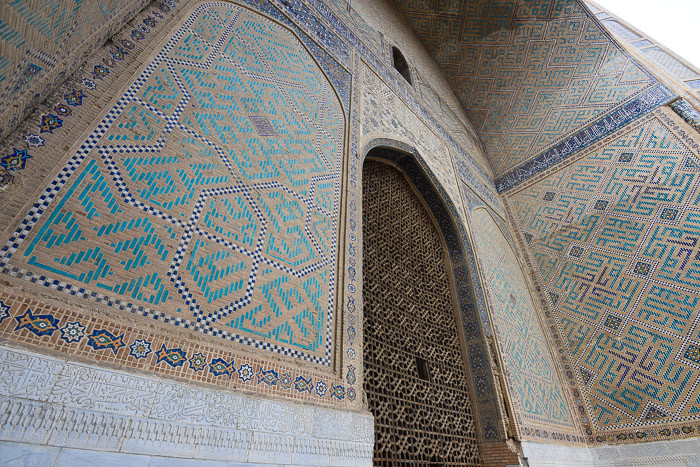

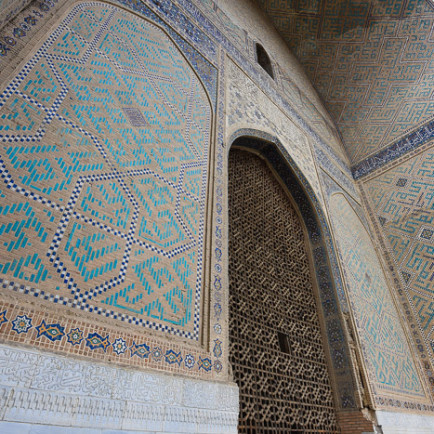

Not everyone was pleased with their work. The architectural historian Robert Hillenbrand notes that in the rush to completion certain liberties were taken, such as replacing missing tiles with fanciful interpretations of what may have existed on nearby tiles—a problem resulted in gibberish when used to restore calligraphic bands. He also faulted the construction of a wall around the mosque that is much taller than the original wall, faced on its exterior by a pastiche of Timuresque brickwork that lacks historical accuracy. In sum, he laments the work as follows:

Description

The Bibi Khanym Mosque, in central Samarkand, is the largest of its kind in central Asia, it was easily the tallest building in Samarkand until the late 20th century. Intended as the congregational (Friday) mosque of Timur's beloved Samarkand, it never truly fulfilled its promise as it was beset from the beginning by structural flaws that became apparent almost as soon as it was constructed. Although dubbed the Bibi Khanym mosque following Timur's chief consort, Saray Mulk Khanum, who is buried nearby, its relationship to Timur's wife remains uncertain. The Spanish ambassador Clavijo, who visited Samarkand from 1404-06, describes it as being built "in honour of the mother of his [Timur's] wife Cano [Bibi Khanym]" Nushin Arbabzadah asserts that Bibi Khanum herself endowed both the mosque and the neighboring madrassa which no longer survives, similar to Gawhar Shad's sponsorship of mosques, madrassas, and other religious institutions a generation later . Blair contends that the mosque was commissioned by Timur but does not indicate for whom it was built

References

Arbabzadah, Nushin. “Women and Religious Patronage in the Timurid Empire.” Afghanistan's Islam: From Conversion to the Taliban, edited by Nile Green, University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2017, pp. 56–70. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1kc6k3q.8.

Blair, Sheila et. al. The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250-1800. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Dani, Ahmad H., et al. History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Paris: UNESCO, 1992.

Golombek, Lisa, and Donald N. Wilber. The Timurid architecture of Iran and Turan. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Hattstein, Markus, and Peter Delius. Islam: Art and Architecture. Germany: H.F. Ullman, 2007.

Hillenbrand, Robert. Islamic Architecture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Hillenbrand, Robert. “Studying Islamic Architecture: Challenges and Perspectives.” Architectural History, vol. 46, 2003, pp. 1–18. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1568797.

Ibbotson, Sophie, and Max Hoare. Uzbekistan: the Bradt Travel Guide. Chalfont St. Peter, Bucks, England Guilford, Connecticut: Bradt Travel Guides Globe Pequot Press, 2016.

Le Strange, Guy. Clavijo: Embassy to Tamerlane 1403-1406. London: George Routledge & Sons, 1928.

MacLeod, Calum, and Bradley Mayhew. Uzbekistan: the Golden Road to Samarkand. Hong Kong & New York: Odyssey Books & Maps. Distributed in the USA by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc, 2014.

Marozzi, Justin. Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2007.

Details

Location

Samarkand, Uzbekistan The approximate location of the site is 39.660675' N, 66.980057' E

Worshippers

10,000

Year of Build

(1399-1405, with later interventions)

Area

109 x 167 meters

Drawings

Map

History

Whatever the truth of the matter, the timing of the mosque's construction—beginning in 1399—corresponds to the year following Timur's wildly successful Delhi campaign that resulted in tremendous spoils brought back to Samarkand, carried on the backs of 95 war elephants (themselves spoils of war) which were later repurposed as heavy-duty haulers at the burgeoning construction site. Although conceived on a massive scale, Timur was in a great hurry to see the mosque finished. Clavijo notes that when Timur looked upon the completed entrance iwan he was dissatisfied with the height and ordered it torn down, executing the amirs responsible for the construction. He then personally took charge of the workmen responsible for one of two deep excavations required for the larger gate, periodically tossing them meat and gold coins to spur on their labors.Construction of the mosque ended in 1405, the same year Timur died from fever during his abortive China campaign. Already, the mosque was showing signs of instability with the dome beginning to crumble and masonry falling on worshippers. The architects, urged on by Timur's oversize ambitions, had made the structure too large to accommodate its own weight and insufficiently stable in an active seismic zone. Timur's generally weak successors, plagued by infighting, had neither the means nor the motivation to shore up the slowly collapsing building. A few made half-hearted additions without resolving the root of the problem, such as Ulugh Beg's gift of an enormous Koran stand that was once mounted in the main chamber but is now on display at the center of the courtyard. Still, its decay was a slow process and it appears to have remained in some form of active use at least through the 17th century when Yalangtush Bakhodur (a.k.a., Yalangtush Bi Alchin) finally built the Tilla Kori mosque and madrassa as a replacement. For centuries thereafter the ruinous mosque languished at the heart of Samarkand, frequently the target of thieves who were eager to repurpose its fine bricks and marble for their own purposes. By the late 19th century the slow stripping of construction material had lead to the near-disappearance of the perimeter walls and galleries.

Further tragedy struck in 1897 when an earthquake rocked Samarkand, bringing down the inner arch of the main iwan. Though still standing, the main dome was riven with cracks and the drum was in a state of near-collapse, as can be seen in the pioneering color photographs of Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii from 1905-1915

Refurbishment and restoration of the ruin began in earnest in the 1970s with Soviet conservationists first taking steps to shore up the collapsing structure. While they made some headway, the bulk of the work took place in the post-Soviet era under the rule of Uzbekistan's first president, Islam Karimov, who lavished funds on restoring Timurid-era buildings as part of a wider plan to redefine Timur as a native-born hero, the pride of all Uzbeks. To these ends, the monument had to be restored in toto so that the legacy of Timur was renewal, not a ruin

Urban and Architectural

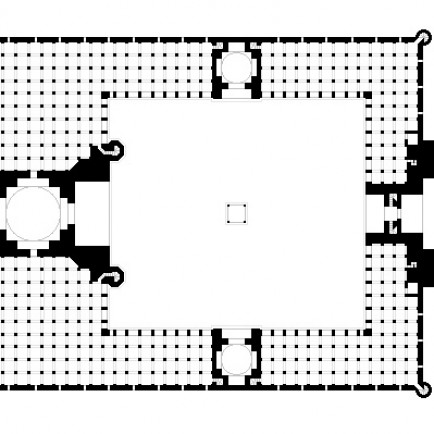

In spite of its size, the design of the Bibi Khanum was not especially innovative. Since the 12th century the four-iwan plan mosque had predominated in Persian lands, and Timur's captive Persian artisans (relocated to Samarkand following the conquest of their homeland) would have been readily familiar with the design, which Bloom describes as a copy of the (now destroyed) mosque of the Ilkhanid sultan Uljaytu at Sultaniyya, Iran. One minor innovation was the addition of domes to the side iwans, turning each into freestanding structures. These side chambers are emblematic of the versatility of Timurid architecture: if viewed in isolation, each are identical to freestanding mausolea, showcasing that for the Timurids, function is not determined by form.The Uzbek conservationists successfully stabilized and restored the collapsing main dome, rebuilt the entrance arch broken in the 1897 earthquake, reconstructed the vanished domes on the side iwans, and everywhere replaced crumbling brick with new masonry indistinguishable from the old.

Not everyone was pleased with their work. The architectural historian Robert Hillenbrand notes that in the rush to completion certain liberties were taken, such as replacing missing tiles with fanciful interpretations of what may have existed on nearby tiles—a problem resulted in gibberish when used to restore calligraphic bands. He also faulted the construction of a wall around the mosque that is much taller than the original wall, faced on its exterior by a pastiche of Timuresque brickwork that lacks historical accuracy. In sum, he laments the work as follows:

Description

The Bibi Khanym Mosque, in central Samarkand, is the largest of its kind in central Asia, it was easily the tallest building in Samarkand until the late 20th century. Intended as the congregational (Friday) mosque of Timur's beloved Samarkand, it never truly fulfilled its promise as it was beset from the beginning by structural flaws that became apparent almost as soon as it was constructed. Although dubbed the Bibi Khanym mosque following Timur's chief consort, Saray Mulk Khanum, who is buried nearby, its relationship to Timur's wife remains uncertain. The Spanish ambassador Clavijo, who visited Samarkand from 1404-06, describes it as being built "in honour of the mother of his [Timur's] wife Cano [Bibi Khanym]" Nushin Arbabzadah asserts that Bibi Khanum herself endowed both the mosque and the neighboring madrassa which no longer survives, similar to Gawhar Shad's sponsorship of mosques, madrassas, and other religious institutions a generation later . Blair contends that the mosque was commissioned by Timur but does not indicate for whom it was built