Hoja Zayniddin Mosque

History

The history of the mosque over the subsequent centuries is murky. Badr and Tupev believe the first phase of painting inside the prayer hall probably took place in the late 16th century. It was subsequently redecorated, making extensive use of the kundal technique sometime in the 17th century, possibly between 1641-1660, as the paintings are stylistically similar to those found in Samarkand's Shir Dor Madrasa and the Tilla Kari. Coincidentally, both works in Samarkand were sponsored by the wealthy official Yalangtush Bi Alchin, who is known to have resided in Bukhara between the construction of the two monuments. This suggests—but does not prove—that he may have been responsible for the redecoration of the Hoja Zayniddin mosque along similar lines. Nothing is known of the fate of the mosque between Yalangtush Bi Alchin's era and the early 1900s. The final period of reconstruction (prior to modern activities) took place between 1913-15. A record of the reconstruction was carved in stone on a waterspout on the east side of the hauz, shown on the final image on this page.

Today, the mosque remains in active use and is an important contributor to the cultural fabric of the city and its residents.

Urban and Architectural

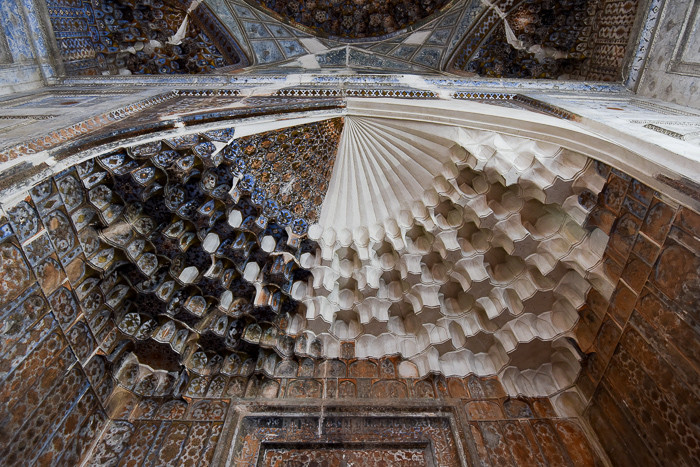

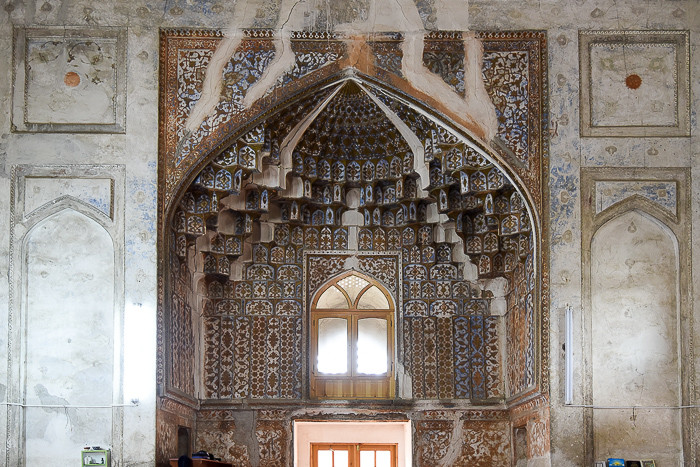

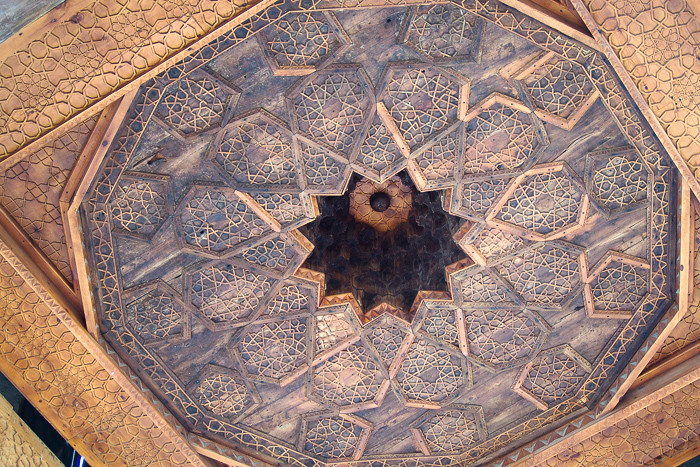

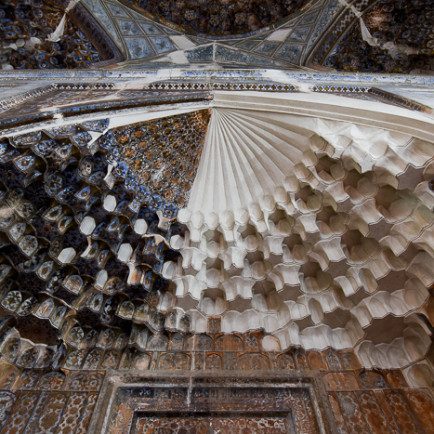

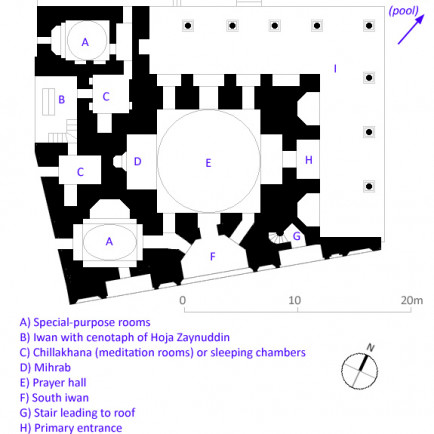

Like all mosques in central Asia, the mosque is organized around an east-west axis canted to the south, toward Mecca, with the qibla wall to the west. The ideal mosque is symmetrical, but the dense urban fabric of 16th century Bukhara likely necessitated a compromise, such that the angle of the building's south and west facades (facing the street) are out of kilter with the primary axis. The building's prayer hall is a spacious domed chamber measuring 9.5 x 9.4 meters, with the dome rising 16 meters overhead with a diameter of 8.2 meters. The main entrance, on the east, includes a deeply recessed chamber crowned with stalactite-like muqarnas vaulting. A similar treatment is used on the qibla wall to the west, which also incorporates at its heart a smaller but a more subdued mihrab (niche) indicating the direction of Mecca. The chamber's north and south walls are pierced with a number of doors and windows, some covered by grilles (pandzhara) to attenuate light and prevent entry by birds. Structurally, the domed chamber is supported by a chahar taq, a set of four sturdy arches perpendicular to one another, forming a square in plan. The chahar taq was introduced to Central Asia only in the late 15th century during the rule of Timur (Tamurlane), suggesting the building was built sometime later. Above the chahar taq, an elegant set of pendentives, squinches, and arches marks the zone of transition from the square walls of the prayer hall to the grand circle of the dome. The body of the dome is inset with four rows of muqarnas vaulting around the outer perimeter, within which thirty-two ribs span tangentially to an inner circle surrounding the dome's apex. Apart from the prayer hall, the building includes a number of smaller rooms that are off-limits to the public. These are mostly small hujras (cells) clustered on the west and south side of the building. According to Jasmin Badr and Mustafa Tupev, some of these chambers may have been used as chillakhana (meditation rooms), whereas others were likely used as living quarters. The presence of living quarters and chillakhana suggests the entire complex may have served as a khanqah, or Sufi lodge, in the manner of similar buildings such as the Nadir Divan-begi Khanqah to the east. Another small room on the northwest contains the cenotaph of Hoja Zayniddin—a man as mysterious in life as in death, as nothing is known about his work or activities. The exterior of the building is dominated on the north and east sides by a wraparound portico supported by wooden columns set on stone footings. Its ceiling is decorated with a variety of star-like patterns rendered in wood. The quality of workmanship is exceptional, on par with quality of similar types of ceilings found in other first-rank monuments in Bukhara, Khiva, and elsewhere.

Northeast of the mosque is a large hauz, or pool, measuring 37 x 26.5 meters. It is shaped like a beveled square with seven steps of limestone, allowing nearby residents to draw water at their convenience. Curiously, the hauz is fed by two separate water sources. One is the adjacent Rud-i Shahr canal, used by a number of monuments in the area. The other is a private covered channel (called a tazar) that was likely directly linked to the Ark (citadel) of Bukhara. As this channel required a run of at least 300 meters through densely-populated areas to reach the citadel, it suggests both a lavish budget for its construction and permission from the ruling authorities to make the connection, strongly implying official sanction or sponsorship of the whole enterprise

Description

The Hoja Zayniddin is a mid-16th century mosque located at the junction of two side streets 300 meters southwest of the Po-i-Kalyan square within the shahr-i-darun, or "inner city". Although its interior houses the grandest dome in Bukhara, very little of substance is known about the origin of the building—both its sponsor and its architect have been lost to the mists of time. Even so, the quality of construction, its proximity to the heart of the city, and its large footprint strongly suggest it was a product of the city's ruling elite, or even of the Khan himself.

References

All images copyright 2019 Timothy M. Ciccone. Photographed February 2019. Badr, Jasmin, and Mustafa Tupev. “The Khoja Zainuddin Mosque in Bukhara.” Muqarnas, vol. 29, 2012, pp. 213–243.,www.jstor.org/stable/23350367. Chuvin, Pierre and Gerard Degeorge. Samarkand, Bukhara, Khiva. Italy: Flammarion, 2001.

Dani, Ahmad H., et al. History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Paris: Unesco, 1992.

Gangler, Anette et. al. Bukhara: the Eastern Dome of Islam. City: Axel Menges, 2004.

Grabar, Oleg. “The Earliest Islamic Commemorative Structures, Notes and Documents.” Ars Orientalis, vol. 6, 1966, pp. 7–46. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4629220.

Hattstein, Markus, and Peter Delius. Islam: Art and Architecture. Germany: H.F. Ullman, 2007.

Hillenbrand, Robert. Islamic Architecture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Knobloch, Edgar. Monuments of Central Asia. London: I.B. Tauris: in the United States and Canada distributed by St. Martin's Press, 2001.

Petruccioli, Attilio, editor. Bukhara: the Myth and the Architecture. Cambridge, MA: Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at Harvard University and MIT, 1996.

Soustel, Jean & Porter, Yves. Tombs of Paradise: The Shah-e Zende in Samarkand and Architectural Ceramics of Central Asia. Hong Kong: Paul Holberton publishing, 2002.

Details

Location

Bukhara, Uzbekistan The approximate location of the site is 39.774731' N, 64.412086' E (WGS 84 map datum).

Owners

both its sponsor and its architect have been lost to the mists of time

Year of Build

(1540s-early 1550s)

Drawings

Map

History

The history of the mosque over the subsequent centuries is murky. Badr and Tupev believe the first phase of painting inside the prayer hall probably took place in the late 16th century. It was subsequently redecorated, making extensive use of the kundal technique sometime in the 17th century, possibly between 1641-1660, as the paintings are stylistically similar to those found in Samarkand's Shir Dor Madrasa and the Tilla Kari. Coincidentally, both works in Samarkand were sponsored by the wealthy official Yalangtush Bi Alchin, who is known to have resided in Bukhara between the construction of the two monuments. This suggests—but does not prove—that he may have been responsible for the redecoration of the Hoja Zayniddin mosque along similar lines. Nothing is known of the fate of the mosque between Yalangtush Bi Alchin's era and the early 1900s. The final period of reconstruction (prior to modern activities) took place between 1913-15. A record of the reconstruction was carved in stone on a waterspout on the east side of the hauz, shown on the final image on this page.

Today, the mosque remains in active use and is an important contributor to the cultural fabric of the city and its residents.

Urban and Architectural

Like all mosques in central Asia, the mosque is organized around an east-west axis canted to the south, toward Mecca, with the qibla wall to the west. The ideal mosque is symmetrical, but the dense urban fabric of 16th century Bukhara likely necessitated a compromise, such that the angle of the building's south and west facades (facing the street) are out of kilter with the primary axis. The building's prayer hall is a spacious domed chamber measuring 9.5 x 9.4 meters, with the dome rising 16 meters overhead with a diameter of 8.2 meters. The main entrance, on the east, includes a deeply recessed chamber crowned with stalactite-like muqarnas vaulting. A similar treatment is used on the qibla wall to the west, which also incorporates at its heart a smaller but a more subdued mihrab (niche) indicating the direction of Mecca. The chamber's north and south walls are pierced with a number of doors and windows, some covered by grilles (pandzhara) to attenuate light and prevent entry by birds. Structurally, the domed chamber is supported by a chahar taq, a set of four sturdy arches perpendicular to one another, forming a square in plan. The chahar taq was introduced to Central Asia only in the late 15th century during the rule of Timur (Tamurlane), suggesting the building was built sometime later. Above the chahar taq, an elegant set of pendentives, squinches, and arches marks the zone of transition from the square walls of the prayer hall to the grand circle of the dome. The body of the dome is inset with four rows of muqarnas vaulting around the outer perimeter, within which thirty-two ribs span tangentially to an inner circle surrounding the dome's apex. Apart from the prayer hall, the building includes a number of smaller rooms that are off-limits to the public. These are mostly small hujras (cells) clustered on the west and south side of the building. According to Jasmin Badr and Mustafa Tupev, some of these chambers may have been used as chillakhana (meditation rooms), whereas others were likely used as living quarters. The presence of living quarters and chillakhana suggests the entire complex may have served as a khanqah, or Sufi lodge, in the manner of similar buildings such as the Nadir Divan-begi Khanqah to the east. Another small room on the northwest contains the cenotaph of Hoja Zayniddin—a man as mysterious in life as in death, as nothing is known about his work or activities. The exterior of the building is dominated on the north and east sides by a wraparound portico supported by wooden columns set on stone footings. Its ceiling is decorated with a variety of star-like patterns rendered in wood. The quality of workmanship is exceptional, on par with quality of similar types of ceilings found in other first-rank monuments in Bukhara, Khiva, and elsewhere.

Northeast of the mosque is a large hauz, or pool, measuring 37 x 26.5 meters. It is shaped like a beveled square with seven steps of limestone, allowing nearby residents to draw water at their convenience. Curiously, the hauz is fed by two separate water sources. One is the adjacent Rud-i Shahr canal, used by a number of monuments in the area. The other is a private covered channel (called a tazar) that was likely directly linked to the Ark (citadel) of Bukhara. As this channel required a run of at least 300 meters through densely-populated areas to reach the citadel, it suggests both a lavish budget for its construction and permission from the ruling authorities to make the connection, strongly implying official sanction or sponsorship of the whole enterprise

Description

The Hoja Zayniddin is a mid-16th century mosque located at the junction of two side streets 300 meters southwest of the Po-i-Kalyan square within the shahr-i-darun, or "inner city". Although its interior houses the grandest dome in Bukhara, very little of substance is known about the origin of the building—both its sponsor and its architect have been lost to the mists of time. Even so, the quality of construction, its proximity to the heart of the city, and its large footprint strongly suggest it was a product of the city's ruling elite, or even of the Khan himself.