Paradise has many gates Mosque

History

Gharem travelled all the way to Vancouver

Canada at the Open-air museum in June to present his concept. Later, “Paradise Has

Many Gates” was erected in the parking lot of Houston’s Station Museum of

Contemporary Art. And during all the summer it stayed in Texas.

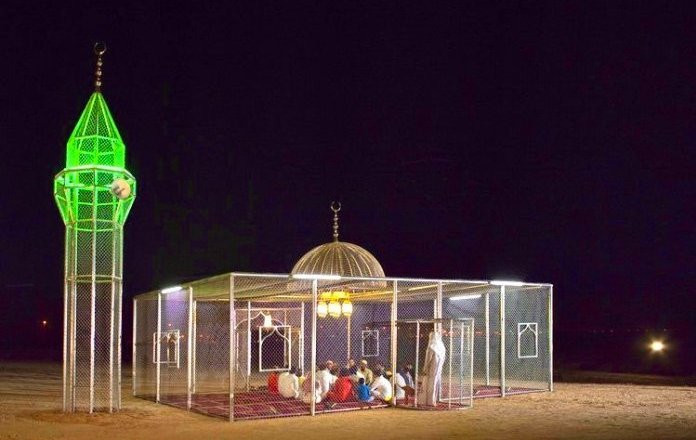

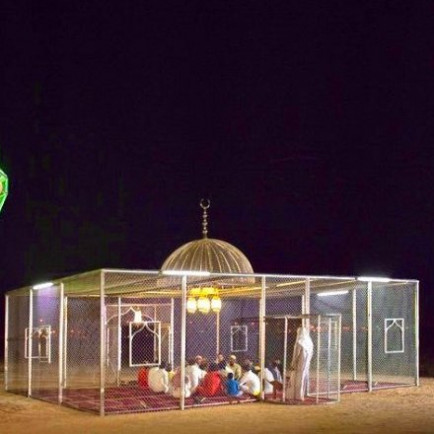

The mosque is made up of severe steel fencing which is normally used by Europe to bar the refugees from entering and by the United States Military at Guantanamo Bay. This idea appealed a lot of people to praise his concept, but it sparked a lot of controversy as well.

While Paradise is relatively rooted in Vancouver (it will be on view through spring 2020), it had a mirage-like first iteration in the Saudi Arabian desert in 2015, when it was dismantled within 24 hours due to concerns about a backlash from fundamentalist clerics. Luckily, Gharem was able to produce a documentary video of the work, complete with a cast of local and foreign workers, that hinted at tensions between the rural and the urban, the foreign and the domestic, as well as larger issues of religious and state authoritarianism. In the social media-saturated kingdom of Saudi Arabia, where 70 percent of the population is under 30, Twitter proved an invaluable ally for Gharem. “At first Sheikh Muhammad al-Munajjid (the hard-line cleric who called for a fatwa against Mickey Mouse in 2008) condemned my work online,” the 33-year-old artist said. But when Saudi Twitter users explained the conceptual aspects of the work, the sheikh withdrew his comments.

Urban and Architectural

The Vancouver Biennale launches its 2018-2020 citywide public art festival this summer—its first installation, unveiled June 20 in the seaside Vanier Park, is Saudi Arabian artist Ajlan Gharem’s Paradise Has Many Gates.

The structure architecturally echoes a traditional mosque though rendered in chain link, making it both airily transparent and ominously evocative of a cage.The dichotomy between form and material evokes the multifaceted conflicts of religious constraint and democratic freedom, embodying the Biennale’s current theme: re-IMAGE-n, which intends to encourage the re-exploration of prevailing belief systems.

Six months after Ajlan Gharem’s Paradise

Has Many Gates was unveiled in Vancouver’s beachfront Vanier Park, the

little mosque made of chain link and steel pipe began to feel like part of the

scenery. In many ways, this installation commissioned by the Vancouver Biennale

acts as a device to reveal landscape, framing views of sky, water, and

mountains that revel in Canadian nature.

The project’s Vancouver incarnation, Gharem

says, is intended as a “community hub,” incorporating input from locals,

weaving by First Nations artisans (its site is a former Indian reservation),

and mandalas by a local Muslim Indo-Canadian artist, Sheniz Janmohamed. The

installation was inspired by and indeed suggests the metal cages found in

Guantánamo, refugee camps, and Trumpian prisons for migrant children, but it

also examines how the community is experienced in public spaces. In a city

where social isolation, rising real-estate costs, and multiculturalism often

intersect in tricky ways, Paradise Has Many Gates succeeds as an

instrument for community interaction. Local First Nations artists who chanted

welcome songs at the opening—each one taking a turn standing at the mihrab (the

prayer niche closest to Mecca)—later displayed some of their weavings on the

grass where bright-red Saudi carpets were initially spread. On any given day,

the interior and exterior of the piece are given new meaning and dimension by

the random passersby who fill its spaces and explore its edges. Playing with

solidity and transparency, the authoritarian and the ephemeral, the work has

become a meta-installation, transcending its original intent as diplomatic rows

between the West and Saudi Arabia cast its ideals in sharp relief.

In contrast to the exquisitely drawn

chandeliers that illuminate the center of Gharem’s mosque, the harsh materiality

of the chain-link exterior underscores material and conceptual tensions.

During the day, the mosque/cage offers framed views of the surrounding Pacific vista. At night, it becomes a jewel-like steel lantern, channelling fragility and gravitas.

Description

Video surveillance.” Someone had scratched out the word “ART” with a black marker and written “Religious” in its place. One is reminded that even as Vancouver’s international art world allure is growing, Canada, too, can suffer from conservatism and xenophobia. After all, it was only a decade ago that, when the Vancouver Biennale presented Dennis Oppenheim’s Device to Root Out Evil—a 25-foot, upside-down, New England-style church with its steeple thrust into the ground—it was driven out of town by “concerned” residents who complained it blocked their view. The Vancouver Parks Board was also inundated with complaints voicing offended Christian sensibilities.

The cage/mosque form also references the prison of identity, and in addition to combatting both Islamophobia and extremism, Gharem hopes his work will continue to be a gathering place for disparate communities. With a schedule of events planned to include local South Asian, Central Asian, and Middle Eastern Muslim as well as indigenous groups, the chain-link mosque on the Pacific has become a hopeful beacon amid a sea of strife. -On a winter’s day, a beaver hurriedly made its way past Gharem’s work en route to a nearby pond. But all is not pastoral in Canada. A nearby sign reads “RESPECT THE ARTWORK. CLIMBING PROHIBITED.

Details

Drawings

Map

History

Gharem travelled all the way to Vancouver

Canada at the Open-air museum in June to present his concept. Later, “Paradise Has

Many Gates” was erected in the parking lot of Houston’s Station Museum of

Contemporary Art. And during all the summer it stayed in Texas.

The mosque is made up of severe steel fencing which is normally used by Europe to bar the refugees from entering and by the United States Military at Guantanamo Bay. This idea appealed a lot of people to praise his concept, but it sparked a lot of controversy as well.

While Paradise is relatively rooted in Vancouver (it will be on view through spring 2020), it had a mirage-like first iteration in the Saudi Arabian desert in 2015, when it was dismantled within 24 hours due to concerns about a backlash from fundamentalist clerics. Luckily, Gharem was able to produce a documentary video of the work, complete with a cast of local and foreign workers, that hinted at tensions between the rural and the urban, the foreign and the domestic, as well as larger issues of religious and state authoritarianism. In the social media-saturated kingdom of Saudi Arabia, where 70 percent of the population is under 30, Twitter proved an invaluable ally for Gharem. “At first Sheikh Muhammad al-Munajjid (the hard-line cleric who called for a fatwa against Mickey Mouse in 2008) condemned my work online,” the 33-year-old artist said. But when Saudi Twitter users explained the conceptual aspects of the work, the sheikh withdrew his comments.

Urban and Architectural

The Vancouver Biennale launches its 2018-2020 citywide public art festival this summer—its first installation, unveiled June 20 in the seaside Vanier Park, is Saudi Arabian artist Ajlan Gharem’s Paradise Has Many Gates.

The structure architecturally echoes a traditional mosque though rendered in chain link, making it both airily transparent and ominously evocative of a cage.The dichotomy between form and material evokes the multifaceted conflicts of religious constraint and democratic freedom, embodying the Biennale’s current theme: re-IMAGE-n, which intends to encourage the re-exploration of prevailing belief systems.

Six months after Ajlan Gharem’s Paradise

Has Many Gates was unveiled in Vancouver’s beachfront Vanier Park, the

little mosque made of chain link and steel pipe began to feel like part of the

scenery. In many ways, this installation commissioned by the Vancouver Biennale

acts as a device to reveal landscape, framing views of sky, water, and

mountains that revel in Canadian nature.

The project’s Vancouver incarnation, Gharem

says, is intended as a “community hub,” incorporating input from locals,

weaving by First Nations artisans (its site is a former Indian reservation),

and mandalas by a local Muslim Indo-Canadian artist, Sheniz Janmohamed. The

installation was inspired by and indeed suggests the metal cages found in

Guantánamo, refugee camps, and Trumpian prisons for migrant children, but it

also examines how the community is experienced in public spaces. In a city

where social isolation, rising real-estate costs, and multiculturalism often

intersect in tricky ways, Paradise Has Many Gates succeeds as an

instrument for community interaction. Local First Nations artists who chanted

welcome songs at the opening—each one taking a turn standing at the mihrab (the

prayer niche closest to Mecca)—later displayed some of their weavings on the

grass where bright-red Saudi carpets were initially spread. On any given day,

the interior and exterior of the piece are given new meaning and dimension by

the random passersby who fill its spaces and explore its edges. Playing with

solidity and transparency, the authoritarian and the ephemeral, the work has

become a meta-installation, transcending its original intent as diplomatic rows

between the West and Saudi Arabia cast its ideals in sharp relief.

In contrast to the exquisitely drawn

chandeliers that illuminate the center of Gharem’s mosque, the harsh materiality

of the chain-link exterior underscores material and conceptual tensions.

During the day, the mosque/cage offers framed views of the surrounding Pacific vista. At night, it becomes a jewel-like steel lantern, channelling fragility and gravitas.

Description

Video surveillance.” Someone had scratched out the word “ART” with a black marker and written “Religious” in its place. One is reminded that even as Vancouver’s international art world allure is growing, Canada, too, can suffer from conservatism and xenophobia. After all, it was only a decade ago that, when the Vancouver Biennale presented Dennis Oppenheim’s Device to Root Out Evil—a 25-foot, upside-down, New England-style church with its steeple thrust into the ground—it was driven out of town by “concerned” residents who complained it blocked their view. The Vancouver Parks Board was also inundated with complaints voicing offended Christian sensibilities.

The cage/mosque form also references the prison of identity, and in addition to combatting both Islamophobia and extremism, Gharem hopes his work will continue to be a gathering place for disparate communities. With a schedule of events planned to include local South Asian, Central Asian, and Middle Eastern Muslim as well as indigenous groups, the chain-link mosque on the Pacific has become a hopeful beacon amid a sea of strife. -On a winter’s day, a beaver hurriedly made its way past Gharem’s work en route to a nearby pond. But all is not pastoral in Canada. A nearby sign reads “RESPECT THE ARTWORK. CLIMBING PROHIBITED.